Triadic Hermeneutics

When we exegete a passage, three poles must always be in mind. First, there is a historical dimension to every text. This includes not only the historical facts a text may claim, but also includes the historical context under which the entire text is to be understood. Second, there is a theological dimension, which speaks not only to the specific theological truths presented, but also considers the contribution a particular text makes to the broad theological grid of the Scriptures. Finally, there is the literary dimension, which includes genre as well as other literary techniques. This hermeneutical triad is taught by Rhadu Gheorghita at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, and it is developed in print by Andreas Köstenberger in an aptly named book, Invitation to Biblical Interpretation: Exploring the Hermeneutical Triad of History, Literature, and Theology.

While recently listening to a presentation on the importance of each element of the triad, I was drawn to a consideration of what happens when we neglect a particular leg of the triad. The following is an attempted identification of what type of reader is presented by each omission:

Literary + Historical – Theological = Reading as an Unbeliever

Let’s say we ignore the theological element of the text. If so, we read the text as an unbeliever reads the text. Across the country there are many who would claim that the Bible is one of the greatest masterpieces of literature (highlighting its literary elements), and they would take seriously its historical claims, while outright rejecting such claims. They may see some consistency in message, but they find no divine author superintending the text or producing a harmonious theological message.

Literary + Theological – Historical = Reading as a Liberal

Those who deny the historical element of the text can be considered liberal in the religious sense of that word. Clearly, they do not deny the historical situatedness of the text; rather, they deny the historical truthfulness of the text. Some may be so sophisticated to argue from a literary or theological standpoint that the text never really meant to speak of historical truth in the way conservatives think it does (e.g., Bultmann’s Demythologizing or Barth’s God’s Time vs our time). Regardless of how they get there, the similarity among liberals is a denial of the text’s historic veracity while maintaining a deep appreciation for the theological and literary aspects of Scripture. Of course, conservatives would argue that without historical moorings, theological propositions are groundless. This is clearly demonstrated in the variety of positions maintained within liberalism.

Theological + Historical – Literary = Reading as an Uninformed Reader

In many ways, this is the least problematic of the deficiencies in the triad. Nevertheless, the results of missing the literary aspects of Scripture can be quite problematic. Of course, everyone who reads the Bible in English translation misses some of the beauty of the original text. Those who have mastered Hebrew will argue that one has never experienced the book of Job appropriately as a literary text unless he has done so in Hebrew (the majority of the text is a poem). Nevertheless, our focus here is not merely on beauty, but is on the literary structures and genres with which Scripture speaks. I am convinced that if there is a place for further development in our hermeneutics it does not reside in the theological or historical side, but rather resides within the literary side. Modern writers write for readers in a literary world, but ancient writers wrote for listeners in an auditory world.

How does that impact the way Scripture is recorded? One key element is the frequent use of inclusions in a text, which signal that a topic has begun and then ended. For instance, in the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus’ first beatitude (5:3) promises the blessing of inheriting the kingdom of heaven, and his last beatitude does the same (5:10). The result of recognizing this literary element is not merely to see that Jesus has ended the beatitude section (which is obvious for other reasons), but is also to indicate that both the characteristics praised as well as the rewards received are of one cloth. That is, Jesus is not suggesting that people who are meek will inherit the earth, while those who are persecuted will have the kingdom of heaven. Instead, it is those who have all of the characteristics (are meek, merciful, persecuted, etc.) that will inherit all of the promises.

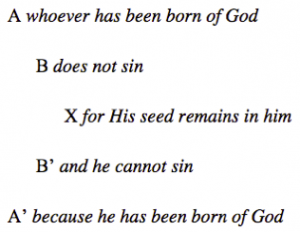

Another frequently used organizational pattern is chiasm, where the author intentionally structures the presentation of material to highlight a central theme or topic. Brad McCoy in his discussion of the topic (click link for more info), highlights a simple chiasm and how it works in 1 John 3:9:

The middle element is usually the most important point of the structure, and is placed there purposefully. Greek and Hebrew did not have italics or bold, and the written language seems to be dependent on oral development to a high degree. Thus, things like Chiasm, which appear quite odd to us, are normal aspects of literature in the Scriptures.

I have focused on this last element, because I think we are aware of the danger or reading like an unbeliever or reading like a liberal. What we most likely will do, however, is read as uninformed people. This may be part of the reason why Köstenberger, in his book on the hermeneutical triad, spends over 500 pages on the literary aspect. How long has it been since you have read a book focusing on the literary dimension of Scripture? It may not be a Copernican revolution in your Bible reading, but it may help you understand better what the Biblical writers—and thus the Holy Spirit—was seeking to communicate to us.

Tim,

Thank you for the stimulating, and mostly, helpful blog post. I know that a blog post should be a brief and not a chapter to be readable and effective. So it is a challenge to compress very important hermeneutical principles in a pithy presentation. Yet I find it it curious that the pithiest of your points is the theological component of the hermeneutical triad. In my opinion, while the point you make may seem obvious, I believe it opens a can of confusing and theologically-biased worms.

The long=standing hermeneutical tradition of DBTS, along with other like-minded schools and bible teachers, is the historical=grammatical method. Evangelicals who adopt and apply this method consistently are anchored on fixed theological moorings that come the Spirit-caused enlightenment in the reception of the Gospel of Christ such as the verbal-plenary inspiration of Scriptures. Still, historical-grammarians, like Grace Theological Seminary (in the past) and faculty of DBTS (presently) have striven for theology to be exegetically-derived from the text. Traditionally, they have warned about erroneous methods of interpretation including a theological/dogmatic method that imposes preconceived theological beliefs/convictions into the meaning of the biblical text (e.g. transubstantiation in John 6, etc.).

After following DBTS’ ministry for several years, I believe that you would agree with the above assessment. My question is why give that first point so little attention when it has been actually a profound, substantive problem among evangelicals in different theological camps (Calvinistic vs Arminian; Cessation vs Charismatic; Non-Covenantal vs Covenantal).

Thank you for reading the comment, your ministry, and for DBTS!

David,

Thanks for the helpful comments. I do in fact agree with what you have said, and I welcome a balancing that your comment makes to the overall post. My concern in the brief post was to seek to identify where most readers of this blog could improve their hermeneutical skills. As was mentioned in the post, the literary aspect is in some ways the least important (at least from the perspective I was taking in the post), yet it is often overlooked.

Tim, thank you for your clarification. Appreciate your teaching ministry.

Dave, I am curious about your response to Tim’s article. You made the statement “In my opinion, while the point you make may seem obvious, I believe it opens a can of confusing and theologically-biased worms.”

Are you saying that utilizing a literary reading of Scripture, as Tim has described, is not wise? Or were you referring to something else in his post opening this can of worms?

If we don’t acknowledge the literary dimension of Scripture we will miss the authorial intent by failing to recognize the variety of genres in which they wrote, which impact the meaning of the text. There can certainly be a debate about how a literary reading impacts the meaning of the text and what it means to read the Bible as literature, but I am having a hard time seeing how we can be faithful to the text without understanding Scripture as literature.

Nathan, I appreciate the response, but it is misplaced. I did not quibble with Tim’s post about the literary dimension of Scripture. I agree with Tim, and with you, about the critical importance of the literary perspective for proper interpretation. My concern was about the role of theology in Bible interpretation and how it might lead to dogmatic, eisegetical interpretation of a biblical text. Read Tim’s response. He even affirmed my comments, and gave a helpful clarification.

I’m wondering why there is no mention of historical interpretation. The Body of Christ has a rich treasure trove of historical interpretations of Holy Scripture. Why would anyone think they can basically set aside the works of all those who have accomplished a tremendous amount of work in the area of biblical interpretation? Blessings!

Wayne,

Thanks for the comment. In a full-orbed discussion of hermeneutics I would certainly develop the role that historical theology plays in our interpretation. It is a double-edged sword, however. We Protestants enjoy going back just as far as Calvin (though Augustine said a few good things), but before then, we find most hermeneutic attempts in church history quite suspect. Anyway, you are right to bring it up!

“We Protestants enjoy”… I know because I am also a Protestant. Thank you replying to my post. Semper Reformanda! To God alone be the Glory!