The Unity of Apostolic Doctrine

Around Easter I contributed a post about Paul’s view of the necessity of Jesus’ resurrection for salvation. The motivation for that post actually came from a Greek exegesis class as we considered 1 Peter. We were discussing 3:18, and we noted that Peter likewise believes the resurrection is necessary for salvation:

This passage teaches that Christ suffered for sins once (a reference to his passion; 18a) with the purpose of bringing us to God (18b). The two participles that follow (θανατωθεὶς and ζῳοποιηθεὶς) indicate the means by which Jesus brings us to God. Notice that Peter believes it is necessary both that Jesus was put to death in the flesh and that he was raised to life in the realm of the spirit in order for men to be rightly brought to the Father.

Accordingly, it was not only Paul who thought the resurrection was necessary for a right relationship with God. Peter and Paul were unified in their theological outlook.

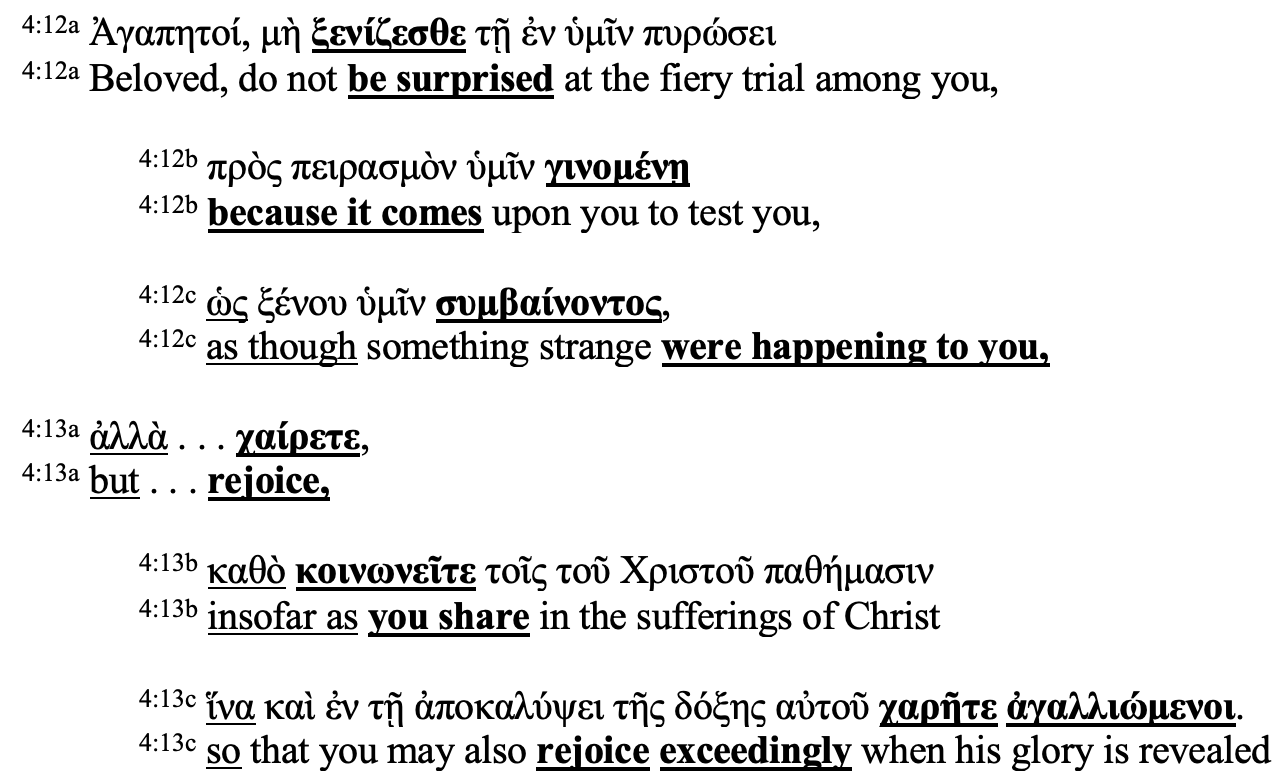

Along the same lines, last week my students in the 1 Peter exegesis course were once more aligning teaching of Peter with those of other NT authors. We were looking at Peter’s teaching on the positive value of suffering. Note the following:

Peter joins both James (1:2) and Paul (Rom 5:3) in expressing the proper Christian response to trials—rejoicing. Of course, there are differences of nuance, but the overall point is strikingly different from the perspective of humanity in general and Judaism in particular. In reference to the latter, some elements of Judaism did seem to speak of the positive, future-world blessings of suffering. Christianity uniquely argued for present rejoicing leading to future rejoicing. In regard to the general world, it appears ridiculous to rejoice in suffering or trial, yet these apostolic authors shared an eschatological view of reality. This world is not the end of all things. To use the image of C.S. Lewis, the end of this life is merely the end of the introduction to the greatest story never told, in which each chapter is better than the last.

The popular theological tradition of our day is to emphasize discontinuity. And this is fair as far as it goes, for Peter does present things differently than Paul, just as an orthodox understanding of inspiration suggests. But while everyone is pointing out the differences between two works of art, the similarities may be overlooked. In this day, too few are engaged in the latter.

In sum, I do not deny that there are advantages to seeing distinctions between biblical writers (i.e., discontinuity). Nevertheless, we do ourselves a disservice when we forget the distinctive commonality of the biblical writers, a commonality derived from their shared community, outlook, and—especially—their shared Lord.