by Mark Ward1

Abstract

After an introduction listing known TR editions, the argument of this paper proceeds in three movements. (1) In the first I summarize the argument for the perfect preservation of the Textus Receptus Greek New Testament used by mainstream “KJV-Only” Christians. (2) In the second I summarize the similar but distinct defenses given for the same text by proponents of a smaller group of Presbyterians and Reformed Baptists which tends to call itself “Confessional Bibliology.” (3) In the third I demonstrate that two particular TR editions carry all but one of the same kinds of differences that occur between the TRs and the critical texts of the GNT. I argue that neither mainstream KJV-Onlyism nor Confessional Bibliology can justify dividing from the majority of evangelical biblical scholars over its doctrines: their views differ only in degree and not in kind from the majority view of textual criticism.

Introduction: Which TR?

Whenever a defender of the King James Version argues that the Textus Receptus (TR) is the providentially preserved text of the Greek New Testament2, a simple question arises: Which TR?

Here is a representative list3 of major TR editions, beginning with Erasmus’ own Novum Instrumentum Omne (1516):

- Erasmus produced five TR editions, in 1516, 1519, 1522, 1527, and 1535.

- Cardinal Ximénes printed the Complutensian Polyglot, which included the first printed Greek New Testament, in 1514. But it was not published until 1522; Erasmus beat it to market by six years. (Note: Erasmus used it to alter a few readings in his 1527 edition.4)

- Simon Colinaeus printed a TR in 1534.

- Robert Stephanus—Colinaeus’ stepson—produced four editions of the TR, in 1546, 1549, 1550, and 1551. The 1550 became the accepted edition (the editio regia) in the English-speaking world.

- Theodore Beza produced five major and five minor editions of the TR between 1565 and 1604.5

- The Elzevir brothers produced seven editions of the TR between 1624 and 1678. The 1633 edition became the standard edition on the European continent—and gave rise to the name “Textus Receptus,” because it called itself “the text received by all.”6

Other editions merit mention here, but it is unclear what exactly should count as a TR: is John Mill’s 1607 Greek New Testament a “TR,” given that his purpose was not to print a perfect Greek text but to report variants—of which he duly supplied 30,000?

The list above will likely suffice, however, to demonstrate that an appeal to “the TR” requires further specification. That list totals, in fact, twenty-eight TRs. No one alive knows precisely how much each differs from the others, for not all have been collated or digitized.7

The KJV translators used two TRs: Stephanus (1550) and Beza (1598). A diligent 19th century scholar with the Dickensian name of Scrivener did indeed collate these, cataloging 111 passages in which the KJV translators chose to follow Beza against Stephanus, 59 in which they did the opposite, and 67 in which they differed from both texts and went with some other reading.8

Consequently, until Scrivener’s work, there was no single edition of the Greek New Testament that perfectly matched the KJV, that reflected the textual-critical decisions of the KJV translators. Scrivener therefore produced yet another version of the TR, one that essentially records all the textual critical choices evident in the KJV. And that means one more TR must be added to the list: Scrivener (1881). This 29th and final TR is the one used today by basically all who prefer the TR.9 But it is, naturally, only one among many TRs. Should Textus Receptus perhaps be Texti Recepti?10

Mainstream KJV-Onlyism and the Textus Receptus

Mainstream KJV-Onlyism11 is to be distinguished from Ruckmanism, the defining feature of which is its belief that the KJV is itself inspired and perfect. Nonetheless, mainstream KJV-Only institutions generally treat the KJV as perfect (their technical term is “preserved”) even if they do not explicitly regard it as such. And there is no doubt that this group treats the Textus Receptus as perfect and immutable.12

R. B. Ouellette, author of one of the most influential and often-cited KJV-Only tracts, quotes George Eldon Ladd giving the standard evangelical view of NT textual criticism, namely that in the absence of divine revelation we are left to our best scholarly lights in evaluating textual variants.13 Ouellette responds:

All answers that come from human scholarship will be imperfect and tentative—this is why we need an Absolute Scripture!14

Mainstream KJV/TR advocates insist—especially when they are speaking to laypeople—that the TR is the fulfillment of Jesus’ promise that every jot and tittle of Scripture would be preserved in providential perfection (Matthew 5:18).

Charles Surrett of Ambassador Baptist College writes in his Certainty of the Words (a title that encapsulates his argument regarding textual criticism),

God does not want His people to look at His Word through eyes of uncertainty, [but] the majority of modern-day textual critics are unsure of the accuracy of their work.…15

While it is certainly possible that humans could err in making copies (and history has proven this to have been the case), it should also be acknowledged that God is capable of superintending the process in such a way that “all the words” of the originals remain intact for believers to access.16

An unpublished white paper written by Bearing Precious Seed Global’s Assistant Director and Translation Director, Steve Combs, acknowledges that “there were textual errors and printing errors in the Received Text when it was first printed.” But Combs posits that “these and other readings were corrected in subsequent editions of the printed text.” He says that

the history of the text from 1516 through 1894 [that is, from Erasmus to Scrivener] is a history of purification and each edition of the Received text brought it closer to perfection. These editions represented steps in the process of God’s preservation of His pure words.17

Combs knows that this may sound like special pleading, even to his KJV-Only readers (Why would a perfectly preserved text need purification, and where was that perfect text during the process?), but he insists that

this is not the same as the process of textual criticism going on today among doubting and unbelieving scholars. This all took place in a context of faith in God’s preservation of His words.18

Combs knows that the KJV New Testament does not match exactly the 1598 Beza text that the translators primarily relied upon. “However,” he says,

the differences between the Beza 1598 text and the KJV represent the pinnacle of the edits made to the TR text and laid the foundation for Scrivener’s 1881 Greek TR edition. No Greek text has ever been produced that is better. Nevertheless, their edits to the Received Text were made in English, not Greek. The KJV translation and its changes in Beza’s 1598 text was an especially important step toward a completely pure printed Greek text.19

This, then, is what we have now in Scrivener’s 1881 TR: a “completely pure” Greek New Testament—given to us by the KJV translators.20

The purpose of the above citations is to show that the mainstream KJV-Only movement—the sector of KJV-Onlyism which appears to be numerically the largest—regularly argues for the perfect preservation of the TR. And their rhetoric consistently pits the certainty available with the forever-settled-in-heaven TR against the instability of the forever-unsettled-upon-earth critical text. If differences among TR editions are acknowledged at all, they are said to be few and minor—or to be transcended by the final purification of God’s Word, which is found in Scrivener’s 1881 TR. To my knowledge, no advocate of mainstream KJV-Onlyism has collated the differences among all printed TRs or has offered principles for determining—when variants between TRs do affect the sense—which reading should be adopted. Countless doctrinal statements from churches, schools, and mission boards confess faith in “the Textus Receptus,” and nearly none specify which TR they confess.21

But the mainstream KJV-Only movement does have an implicit answer to the question, “Which TR?” There is one edition of the Greek New Testament that it consistently uses in its various educational institutions: Scrivener’s TR, particularly the edition put out by the Trinitarian Bible Society. They also, therefore, have an implicit principle for choosing among TR readings, namely divine providence through the apparent blessing of the KJV.22 In other words, the answer of mainstream KJV-Onlyism to the question, “Which TR?” is: “The KJV.”

Confessional Bibliology

Proponents of “Confessional Bibliology” take a different path to a similar but not identical viewpoint. They follow the more scholarly tradition23 of Dean Burgon, E.F. Hills, Wilbur Pickering, and Theodore Letis, and they regularly and publicly resent comparisons to mainstream KJV-Onlyism. Currently, the three leading proponents of this viewpoint are probably Jeffrey Riddle,24 Robert Truelove,25 and the late Garnet Milne.26

Confessional Bibliology (CB) reacts to the same concerns addressed by KJV-Onlyism (indeed, the leading CB proponents vigorously defend the King James Version27). They point to the apparent instability of the modern critical text;28 the loss of the longer ending of Mark and the Pericope Adulterae; the very idea that centuries of God’s people may have gone without some of God’s words. All of these factors lead CB proponents away from the mainstream evangelical viewpoint on textual criticism. But a “confessional” approach to bibliology is not a path open to mainstream KJV-Onlyism, which is generally independent Baptist and therefore not confessional. It is Reformed Baptists and conservative Presbyterians who make up most of the adherents of Confessional Bibliology.

The Westminster Confession of Faith (identical here to the Second London Baptist Confession of 1689) provides the path necessary for confessional Christians to move away from the majority evangelical view of Greek New Testament textual criticism:

The Old Testament in Hebrew…and the New Testament in Greek…, being immediately inspired by God, and, by His singular care and providence, kept pure in all ages, are therefore authentical; (Matt. 5:18) so as, in all controversies of religion, the Church is finally to appeal unto them.29

CB asks: What Greek New Testament text were the Westminster divines confessing to be “kept pure in all ages”? It answers: the Textus Receptus.30 This, they say, was the text actually in use at the time of the confession.31

CB is still a tiny minority viewpoint in evangelical circles. To mention this fact is no insult; a view is not wrong because it is held only by a few. In fact, CB merits discussion because its leaders are gifted men, it appears to be growing, and because it is finding some young adherents. My impression is admittedly unscientific, but I believe CB holds some attraction for those influenced by the Young, Restless, and Reformed movement.32 As these younger men (now around age 40) take leadership in churches, a significant number are digging deeper into a Reformed tradition that they first entered through soteriology. Next comes ecclesiology, and then, for a few, bibliology. Protestant pluralism and doctrinal downgrade you will always have with you, and people react differently to them: some resort to assorted confessionalisms.33 A stable tradition is appealing.

So after citing WCF 1.8, the next major phase in the CB argument is often an appeal to a major exemplar of the English Reformed tradition: John Owen—particularly his “Of the Integrity and Purity of the Hebrew and Greek Text of the Scripture.”34 CB sees Owen’s discomfort with another scholar’s choice to list hundreds of NT textual variants as an indication that other 17th century British Reformed dogmaticians meant to defend the TR in WCF 1.8. Owen indeed spoke of “the purity of the present original copies of the Scripture, or rather copies in the original languages, which the church of God doth now and hath for many ages enjoyed as her chiefest treasure.”35

Robert Truelove, for example, builds on Owen, arguing that his statements

demonstrate that those in the era of the great English confessions believed their Received Text was a functionally pure text in spite of any variant issues which they saw as so trifling as to be virtually dismissive of them. It is therefore inconceivable that men like…Owen would accept many of the conclusions found in the modern Critical Text.36

The late Theodore Letis, a skilled and vivacious writer, makes a nearly identical appeal in his The Ecclesiastical Text: Criticism, Biblical Authority & the Popular Mind.37 Letis makes an ardent case that orthodox theologians were always united in investing authority in the apographa (the copies) and not in the autographa (the original written copies of individual Bible books).

This generally leads CB proponents next—and Letis is here the best example—to pillory B. B. Warfield. Warfield, Letis says, foolishly adopted the German “lower criticism” of the New Testament text, not realizing that it was just as unorthodox as the German “higher criticism” of book authorship that he opposed. Warfield, Letis says, tried to save the Bible from higher critics by “relegat[ing] inspiration to the inscrutable autographs of the biblical records.”38

Hills and Letis both relate lengthy histories of biblical criticism which promote a guilt-by-association thesis—one Letis, especially, makes explicit:

While everyone in confessional ranks attempted to resist to the death the invasion of the nineteenth-century German higher criticism with its quest for the historical Jesus, they nevertheless unwittingly gave way to the process of desacralization [of the Bible] by assuming the safe and “scientific” nature of the quest for the historical text. The…entire history of the influence of Biblical criticism on confessional communities is but a working out of this theme, with adjustment after adjustment taking place, until the original paradigm of verbal inspiration evaporates and no one is so much as aware that a change has taken place.

In other words, textual criticism, at least as practiced by mainstream biblical studies, must necessarily lead to the death of inspiration.

But proponents of CB do sometimes acknowledge the necessity of one specific kind of textual criticism: that between TR editions. E.F. Hills shows more interest in differences between TR editions than any other writer I could locate.39 He does not offer a full collation of any such editions, but he is aware of Scrivener’s and Hoskier’s work doing just this,40 and he briefly discusses quite a number of TR variants.

The key quotation on this topic comes from Hills’s Text and Time (this is the original, prepublication title of what then became The King James Version Defended). These words and concepts are frequently quoted by contemporary CB proponents, and are therefore worth quoting at length:

God’s preservation of the New Testament text was not miraculous, but providential. The scribes and printers who produced the copies of the New Testament Scriptures and the true believers who read and cherished them were not inspired, but God-guided. Hence, there are some New Testament passages in which the true reading cannot be determined with absolute certainty. There are some readings, for example, on which the manuscripts are almost equally divided, making it difficult to determine which reading belongs to the Traditional Text. Also, in some of the cases in which the Textus Receptus disagrees with the Traditional Text, it is hard to decide which text to follow. Also, as we have seen, sometimes the several editions of the Textus Receptus differ from each other and from the King James Version. And, as we have just observed, the case is the same with the Old Testament text. Here, it is hard at times to decide between the kethibh and the keri and between the Hebrew text and the Septuagint and Latin Vulgate versions. Also, there has been a controversy concerning the headings of the Psalms.

In other words, God does not reveal every truth with equal clarity. In biblical textual criticism, as in every other department of knowledge, there are still some details in regard to which we must be content to remain uncertain. But the special providence of God has kept these uncertainties down to a minimum. Hence, if we believe in the special providential preservation of the Scriptures and make this the leading principle of our biblical textual criticism, we obtain maximum certainty, all the certainty that any mere man can obtain, all the certainty that we need. For we are led by the logic of faith to the Masoretic Hebrew text, to the New Testament Textus Receptus, and to the King James Version. But what if we ignore the providential preservation of the Scriptures and deal with the text of the holy Bible in the same way in which we deal with the texts of other ancient books? If we do this, we are following the logic of unbelief, which leads to maximum uncertainty.41

The distinction between “miraculous” (i.e., perfect) and “providential” preservation is a leading part of Hills’s answer to the question, “Which TR?” Hills looks squarely at the amount of uncertainty provided by his viewpoint. He acknowledges both differences among TR editions and differences between them and the KJV. But he labels these differences as “minimum” and “providential” and therefore acceptable. He takes the amount of uncertainty generated by the critical text view and labels it “maximum.” He does not offer guidance for how to determine when the number of variants passes from minimal to unacceptable. He does not offer guidance, either, on how to distinguish providence that confers authority from providence that does not: indeed, surely all New Testament manuscripts now extant were “providentially preserved” by God. But Hills does offer a principle by which to distinguish the false readings from the true in those few places where “the TR” divides: the King James Version.

Hills uses precisely the same argument used by mainstream KJV-Onlyism. He appeals to God’s providential use of the KJV as validation of its textual-critical decisions.

But what do we do in these few places in which the several editions of the Textus Receptus disagree with one another? Which text do we follow? The answer to this question is easy. We are guided by the common faith. Hence, we favor that form of the Textus Receptus upon which more than any other God, working providentially, has placed the stamp of His approval, namely, the King James Version, or, more precisely, the Greek text underlying the King James Version. This text was published in 1881 by the Cambridge University Press under the editorship of Dr. Scrivener.42

Hills holds to this principle even when he feels that it is awkward. For example, he acknowledges that both Erasmus and the KJV translators chose readings that ultimately came from the Latin Vulgate and not from the “Traditional Text” of the New Testament or the majority (Byzantine) manuscripts he earlier praised. Indeed, Hills defends Erasmus’s choice to include readings that occur in no extant Greek NT manuscripts—famously, “book” instead of “tree” in Revelation 22:19. But he concludes that Erasmus was “guided providentially by the common faith to follow the Latin Vulgate.”43 In other words, God made emendations to his own Greek text through a Catholic scholar who opposed Luther, and then he further validated those emendations through the KJV:44 “Sometimes, the King James translators forsook the printed Greek text and united with the earlier English versions in following the Latin Vulgate.”45 In these places, “the King James Version ought to be regarded not merely as a translation of the Textus Receptus, but also as an independent variety of the Textus Receptus”46—the ultimate and authoritative variety, for on it God has placed “the stamp of His approval.”

A premier influence on Confessional Bibliology—quoted repeatedly by its contemporary proponents precisely when they are asked, “Which TR?”—uses ultimately the same logic as the KJV-Only world more generally: (1) Inspiration demands perfect preservation; (2) we discover which jots and tittles are the perfectly preserved ones by looking for which Bible God has used the most often; (3) the KJV is clearly that Bible; (4) the texts underlying it must therefore also bear the divine imprimatur and be perfect.

In sum, though Confessional Bibliology speaks on a noticeably higher academic level than mainstream KJV-Onlyism and repeatedly claims to be distinct from it,47 and though CB proponents are indeed much more careful to distinguish their defense of a Greek New Testament from that of a particular English translation of it, they boil down to the same viewpoint—they pick the same final standard. I am compelled to make the same judgment of them that Peter Williams made of Letis: Confessional Bibliology is merely an “up-market” KJV-Onlyism.48

The two groups also trade on the same basic tropes: Confessional Bibliology argues that the Bible in the hand is superior to the manuscripts in the bush; in other words, it argues that the pure text of Scripture has always been available to those among God’s people who look for it.49 Everywhere CB proponents simplify the debate by reifying “the TR” (or “the Ecclesiastical Text” or “the Traditional Text”), as if it is one stable entity rather than a collection of variants among which editors and translators must make choices.

CB adds its own distinctive advances, however, producing certain rallying cries not commonly found in mainstream KJV-Onlyism. They, of course, appeal to WCF 1.8: the text of Scripture is “kept pure in all ages.” CB proponents use language not generally found in mainstream KJV-Onlyism, namely autographa (original copies of NT books) and apographa (reliable copies of NT books). They also contrast their “supernatural” view of textual transmission with the “naturalistic” view of textual criticism practiced by the great majority of evangelical biblical scholars.50 And they argue that the same logic used for canon ought to be used for text: use in the church of self-authenticating readings constitutes validation by the Spirit.51 They apply that logic to translations as well.

To summarize, Confessional Bibliology’s answer to the question, “Which TR?” is “The KJV.”

Stephanus vs. Scrivener and Differences of Degree vs. Differences of Kind

Mainstream KJV-Onlyism usually treats the KJV as perfect and therefore certain. It appears generally unaware that there are differences among KJVs and TRs. Confessional Bibliology usually treats the TR as essentially perfect and therefore certain. When it acknowledges differences among TR editions (which to its credit it does regularly do), it dismisses them as “trifling.” Hills, an influence over both camps, says that variants between TRs “do not materially affect the sense of the passages in which they occur. They are only minor blemishes which can easily be removed or corrected in marginal notes.”52 He admits the principle that, in areas of uncertainty, it is appropriate at times to say, “These variants are insignificant.”

But each camp consistently represents the variants between “the TR” and various critical texts (CTs) as massively significant—and, of course, massively numerous. Each group cuts a wide and deep ditch between “the TR” and all present and future critical editions.53

It is quite likely that the variants between the TRs and the CTs are more numerous than those among the TRs—though this cannot be known with certainty until collations are made of all the various TR editions. But are the differences between the two textual traditions (TR and CT) massively significant? Are they different not merely in degree but also in kind?

Owen himself suggests something like a plan for answering this question: “A man might…take all the printed copies he could get of various editions, and gathering out the errata typographica, print them for various lections.”54

This paper will not look at typographical errors but at “various lections” between two TR editions; and this paper is driving at a point: TR editions feature the same kinds of variants as those that occur between the CT and TR; the two viewpoints differ only in degree and not in kind.

We will examine all the kinds of differences between two of the twenty-eight editions of the TR, probably the most significant editions in existence: (1) Stephanus’ 1550 TR, which was the most widely used GNT in England during the time of the KJV translators and (2) Scrivener’s TR, the most widely used TR today. By comparing these two TRs we will see where the KJV translators decided against the most significant TR edition of their day. We will see, then, where the KJV translators did the work of textual criticism on their main TR.

The discrepancies between these two TRs are categorized into kinds below: spelling differences, tense differences, word differences, etc. We will proceed through these categories in order of significance, from least to greatest.

_Spelling Differences 55

There are multiple spelling differences between the Stephanus TR and the Scrivener TR. Among them (Stephanus is listed first, then Scrivener, in each case):

- Ναζαρέτ (nazaret) vs. Ναζαρέθ (nazareth) (Matt 2:23; 4:13; etc.)

- Βεελζεβοὺλ (beelzeboul) vs. Βεελζεβοὺβ (beelzeboub) (Matt 10:25)

- Ἑστὸς (estos) vs. ἑστὼς (estōs) (Matt 24:15)

Any TR defenders who read this article will likely—and rightly, in this writer’s opinion—dismiss this first category of TR discrepancies as utterly insignificant. These spelling differences make no difference for meaning and no difference in translation. If there is a difference between Beelzebul and Beelzebub, we today do not know what it was.56

Differences That Do Not Have to Show Up in Translation, but Could

There is a ὅτι (hoti), at Matthew 9:33 that is present in Stephanus but not in Scrivener. This makes no difference in meaning, though an unnecessarily fastidious translator could try to reflect it. It would mean the difference between “They said it was never so seen” (Scrivener) and “They said that it was never so seen” (Stephanus).

In this writer’s opinion, TR defenders will and should dismiss the significance of such differences, much as they will and should with spelling differences. The word ὅτι basically functions here like a quotation mark and not a word (a so-called ὅτι recitativum). It is contextually redundant: no one could possibly confuse the meaning of the clause with or without it. This difference is less than minor.

Differences in Word Order That Do Not Affect Meaning

In 1 Timothy 1:2, Stephanus reads “Christ Jesus” (Χριστοῦ Ἰησοῦ) where Scrivener reads “Jesus Christ” (Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ). Once again, there is no difference in meaning; but there is a clear difference demanded in English translation. And once again, TR defenders from KJV-Onlyism and Confessional Bibliology are likely justified in dismissing this difference as insignificant.

Differences That Amount to Simple Redundancies

Revelation 7:14 is slightly fuller in Stephanus than in Scrivener. Stephanus reads, “These are they which came out of great tribulation, and have washed their robes, and made their robes (στολὰς αὐτῶν) white in the blood of the Lamb.”57 The KJV—and therefore Scrivener—reads, “These are they which came out of great tribulation, and have washed their robes, and made them (αὐτὰς) white in the blood of the Lamb.” It is clear what the antecedent of “them” is in Revelation 7:14 is. Stephanus makes something that is unmistakable doubly unmistakable. Once again, TR defenders are justified in seeing this as a distinction without a difference.

Differences in Number (Singular vs. Plural)

- There is a singular vs. plural discrepancy at Matthew 10:10; Jesus either tells his disciples not to bring a “staff” (ῥάβδον) on their mission (Stephanus) or not to bring “staves” (ῥάβδους) on their mission (Scrivener).

- There is another such variant in Matthew 21:7, ἐπεκάθισεν vs. ἐπεκάθισαν—the difference between one person setting Jesus on the colt for the triumphal entry (Stephanus) and two or more people doing it (Scrivener).

- Similarly, in 2 Peter 2:9 Jesus knows how to rescue the godly from either “temptation” (πειρασμoῦ, Stephanus) or “temptations” (πειρασμῶν, Scrivener).

TR defenders might struggle a bit more here than they did with the previous categories of difference; it may be that they will not or even should not dismiss this category as insignificant. There are places in the New Testament where the difference between singular and plural matters. Famously, Paul’s interpretation of the Genesis 13:15 seed metaphor in Galatians 3:16 turns precisely on its number—and, indeed, TR defenders of all stripes appeal to precisely this verse as demanding perfect, every-jot-and-tittle preservation. But quite clearly, no doctrine rides on the above three variants between Stephanus and Scrivener. From that perspective they are trifling.

Differences of Person in Pronouns

In Mark 9:40, Stephanus reads, “The one who is not against you (ὑμῶν) is for you (ὑμῶν),” while Scrivener reads, “The one who is not against us ( ἡμῶν) is for us (ἡμῶν).” It is quite clear, either way, that Jesus means to include himself among the people to whom this proverbial saying applies. There is a definite difference here in translation, but not in meaning.

Tense and/or Mood Differences in Verbs

- There is a present vs. an aorist participle discrepancy in Matthew 13:24. The difference is between a sower who “is sowing” (σπείροντι) seed (Stephanus) and one who “sowed” (σπείραντι) seed (Scrivener).

- In Revelation 3:12 there is a tense and mood difference between καταβαίνει (Scrivener) and καταβαίνουσα (Stephanus). Either the New Jerusalem “comes” out of heaven or it “is coming” out of heaven.

Tense can be very significant for meaning—such as the difference between “You are saved” and “You will be saved.” But it is difficult to see a significant difference in meaning in the above two passages. Whether we envision the sower as now sowing or as having already gone out to sow, the picture is precisely the same. In Revelation 3:12, too, there is no real difference in meaning between the two TRs. “Time signatures” in apocalyptic literature are often obscure. And whether Jesus is speaking in the prophetic present or the prophetic aorist, clearly the New Jerusalem has not come yet—but will.

Interlude

Before we arrive at the three most significant categories of difference between the two TRs we are examining, it will be helpful to take a brief intermission to hear from the Trinitarian Bible Society, one of the most prominent institutions dedicated to defending the TR and the KJV—and a group respected by both mainstream KJV-Onlyism and Confessional Bibliology. TBS is aware of such differences and does indeed dismiss them, as this paper has recommended that they do:

The Greek Received Text is the name given to a group of printed texts, the first of which was published by Desiderius Erasmus in 1516. The Society uses for the purposes of translation the text reconstructed by F.H.A. Scrivener in 1894.

As the scope of the Society’s Constitution does not extend to considering the minor variations between the printed editions of the Textus Receptus, this necessarily excludes the Society from engaging in alteration or emendation of the Hebrew Masoretic and Greek Received Text on the basis of other Hebrew or Greek texts. Editorial policy and practice will observe these parameters.58

TBS, the publishing ministry that supplies printed TRs to all varieties of KJV-Onlyism, says that all differences between TR editions are “minor.” And here is the key rhetorical point we have been driving toward: by dismissing all differences among TRs as minor, they have implicitly agreed to dismiss a huge portion of the differences between the TRs and the critical texts. Indeed, how many places of textual variation are left if the above seven kinds of differences are dismissed?59

Every kind of difference visible between TRs is visible, too, between the two major exemplars of the TR and CT traditions, namely Scrivener’s TR and the Nestle-Aland 28:60

Spelling Differences. There are many insignificant spelling differences between the TR and the CT, such as Δαβὶδ (Scrivener) vs. Δαυὶδ (NA28).

Differences That Do Not Have to Show Up in Translation, but Could. There are many differences between the TR and the CT which a fastidious translator could reflect but does not have to. Τοῖς οὐρανοῖς (Scrivener) in Matthew 23:9 could be rendered as a plural—“in the heavens,” which would distinguish it from “in heaven” (ὁ οὐράνιος, NA28). (Note, however, that the KJV translators themselves opt to render the plural as a singular, presumably for reasons of English style.)

Differences in Word Order That Do Not Affect Meaning. There are many differences in word order between the TR and CT that do not affect meaning. Dozens of times, the very example adduced above—“Jesus Christ” vs. “Christ Jesus”—differs between the two. Consider also “flesh and blood” (Scrivener) vs. “blood and flesh” (NA28) in Hebrews 2:14.

Differences That Amount to Simple Redundancies. There are many differences between the TR and CT that amount to simple redundancies. The very first textual variant between them, Matthew 1:6, is one example. The TR calls David “the king” twice; the CT calls him “the king” only once. David is not any more or less a king by being named “king” once or twice. One of the most common observable differences between the TR and the critical text is that the TR, as a generally later text, tends to fill out and specify what’s already clear in the earlier texts that make up the baseline of modern critical editions.

Differences in Number (Singular vs. Plural). There are many number differences between the TR and CT, too, that make no difference at all for the meanings of the passages in which they occur. Certainly, no doctrine is affected. The KJVParallelBible.org project reminded this writer over and over again that a great deal of the Bible is not directly doctrinal. It is not thereby unimportant—but does it really matter whether Peter makes the tents on the Mount of Transfiguration (ποιήσω, NA28) in Matt 17:4 or whether he volunteers James and John to help (ποιήσωμεν)? If minor differences of number between TRs are acceptable, they ought in principle to be acceptable between the TR and the CT.

Differences of Person in Pronouns. One of the most frequent differences between the TR and the CT is a switch between first- and second-person among pronouns. The TR reads, “We, brethren…, are the children of promise.” The CT reads, “You, brethren…, are the children of promise” (Gal 4:28). Differences in pronunciation in various regions and eras of the ancient world may have led to a common confusion between ἡμῶν and ὑμῶν. But naturally, NT writers such as Paul counted themselves among the saints, and so “you” and “we” often refer to the same set of people.

Tense and/or Mood Differences in Verbs. There are regular tense and/or mood differences between the two texts. One difference that occurs several times is the so-called “historical present.” Matthew 13:28 in the NA28 has a master’s servants “say” (λέγουσιν) something to him; Scrivener reads that they “said” (εἶπον) something to him.61

Interlude Conclusion. The mainstream evangelical view of textual criticism explains rather well why the kinds of differences that occur between TR editions occur also between the TR and the CT: both are the results of textual criticism on copyist errors over the centuries. The various TR editions used a smaller number of manuscripts, and their processes for evaluation, their rationale, were at an earlier stage of the development of the science of textual criticism. If, as TR defenders commonly argue, the textual critical canons that have guided the formation of modern critical texts are unacceptably subjective,62 one wonders whether the textual critical decisions made by Erasmus, for example, are any better for having been (at least initially) accidental.63 Going-public-first should not be a textual critical canon, especially given some of the sui generis readings Erasmus introduced into the text from the Vulgate (see discussion of Rev 22:19 above).

Differences in Words That Produce Differences in Meaning

Many TR defenders will likely feel comfortable dismissing as insignificant the kinds of variants in the seven categories that preceded the interlude. Most differences between the two TRs in this paper are simply and obviously not significant. But there are a few which are more difficult to label “minor”—though the TBS does so. There are places where Stephanus and Scrivener use wholly different words requiring noticeably different translations. Some principle of evaluative judgment must be brought in for each case to decide which text will be translated and which will be ignored or go into a footnote.

- One example is Matthew 2:11. This is the difference between the wise men coming and “finding” (εὗρον) Jesus with Mary (Stephanus) and coming and “seeing” (εἶδον) Jesus with Mary (Scrivener). The overall sense of the passage is not affected, but both readings cannot be perfect preservations of the original.

- 1 Peter 1:8 is similar. Whether Peter’s hearers loved Jesus without “knowing” (εἰδότες) him (Stephanus) or without “seeing” (ἰδόντες) him (Scrivener) makes very little difference: these Christians became Christians without ever meeting the Savior during his earthly ministry. But, again, both cannot be original.

- In 1 Timothy 1:4, Scrivener’s GNT speaks of “the godly edifying (οἰκονομίαν) which is by faith”; Stephanus (in agreement with the NA28) speaks of a “stewardship (οἰκοδομίαν) of God which is by faith.” Stephanus’ reading is somewhat awkward; the KJV translators went with the more contextually natural reading, even though it is found in only a small minority of Greek manuscripts.

- In 1 John 1:5, “God is light” is either the “promise” (Stephanus) or the “message” (Scrivener) that John is declaring. The difference is only two letters in Greek (ἐπαγγελία vs. ἀγγελία), but both cannot be original. In my judgment, the KJV translators chose the more contextually appropriate variant.

- In 2 Corinthians 11:10, Paul’s boasting will either not be “sealed” (σφραγίσεται, Stephanus) or not be “silenced” (φραγήσεται, Scrivener). The former makes poor sense; surely the KJV translators made the right textual-critical decision here (against that of the Bishop’s Bible which they were tasked with revising64).

- In 2 Thessalonians 2:4, the man of lawlessness sets himself up against either “all the things that are called God” (πάντα, Stephanus) or “all that is called God” (πᾶν τὸ, Scrivener). Meaning does not seem to be affected, but translation is; and each cannot be original.

- In Philemon 1:7, did Paul feel “gratitude” (χάριν, Stephanus) or “joy” (χαρὰν, Scrivener)? Surely he felt both, but which did he write? Which TR is correct? Context—internal evidence—is insufficient to determine the answer. Each works. The KJV translators chose “joy.”

- Hebrews 9:1 records another difference between our two TRs. A number of manuscripts beginning in the eleventh century, along with at least one manuscript of the Latin Vulgate, say “The first tabernacle (σκηνή) had ordinances of divine service.” Stephanus adopts this reading. Scrivener, reflecting the choice of the KJV translators, has nothing where Stephanus had “tabernacle.” The sentence is elliptical, and natural English tends to require translators to insert a word. The KJV translators obliged, putting “covenant” in roman type (the equivalent of italics in some modern-day Bible translations). In my judgment, “tabernacle” is a metonymy for the Mosaic covenant. So the two verses mean the same thing—but the KJV translators elected to insert italics when they could have used Stephanus’ reading.

- James 5:12 is very interesting. It provides a perfect example of the kind of difference that regularly occurs between the TRs and the critical texts. Stephanus’ TR warns readers not to swear, “lest you fall into hypocrisy” (ἵνα μὴ εἰς ὑπόκρισιν πέσητε). Scrivener’s TR warns them not to swear “lest you fall under condemnation” (ἵνα μὴ ὑπὸ κρίσιν πέσητε).65

- In Revelation 7:10, the redeemed cry out “Salvation!” either “to our God who sits on the throne” (τῷ Θεῷ ἡμῶν τῷ καθημένῳ ἐπὶ τοῦ θρόνου, Scrivener) or “to the one who sits on the throne of our God” (τῷ καθημένῳ ἐπὶ τοῦ θρόνου τοῦ θεοῦ ἡμῶν, Stephanus). It is possible there is a difference in meaning here: perhaps Stephanus’ reading could be saying that the Son sits on God’s throne, but that would seem odd given that the redeemed add additional praise to “the lamb.”66

I do not relish as an inerrantist telling laypeople that the biblical manuscript tradition contains variants. So I am eager to point out that the two TRs I compared are almost as similar as it is possible for two books printed without the aid of a computer to be. The overall sense of most passages that contain discrepancies is very similar, no matter which reading is chosen. But the differences are not random or meaningless, not the equivalent of typos. They do yield different translations—and someone must choose which TR variant to translate and which to exclu__de or put in the margin. The KJV translators had to. Erasmus had to.

Everyone who prints a Greek New Testament or a Bible translation has to. The problem of textual criticism will not go away. Being “TR-Only” does not solve that problem when the question is, Which TR?

TR positions are typically used to remove uncertainty, to obviate all need for humans to “sit in judgment” over the text of Scripture. But this will not work when “the” TR is not itself absolute. And if wholly different words are “trifling differences” when they occur between TRs but “corruptions” when they occur between the TR and CT, one wonders where the line is between trivial and corrupt.

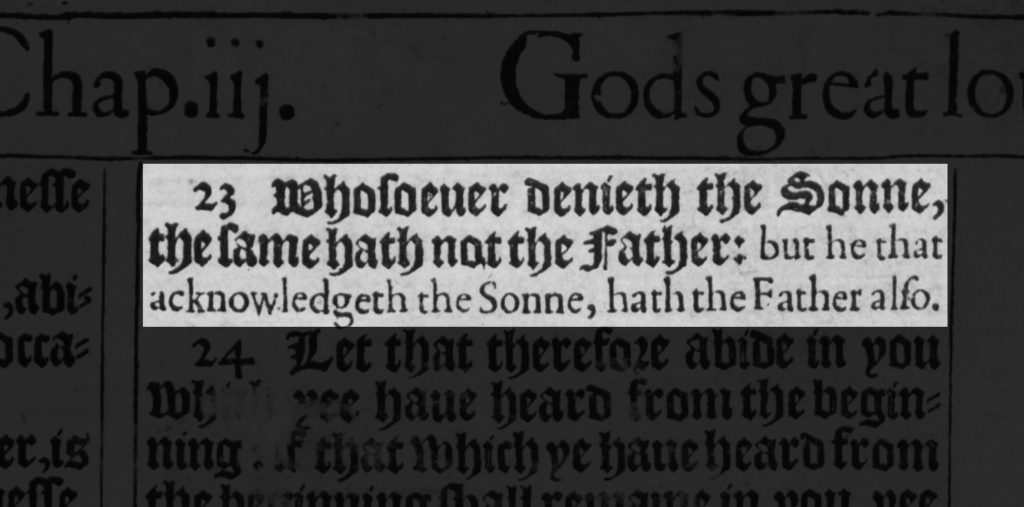

Missing Clauses

This category of difference contains one example: 1 John 2:23. In this verse, Scrivener includes an entire sentence that is not present in Stephanus: ὁ ὁμολογῶν τὸν υἱὸν καὶ τὸν πατέρα ἔχει. The KJV renders this phrase in the 1611 first edition as, “but he that acknowledgeth the Sonne, hath the Father alſo.” Uniquely in the entire King James Version, the translators placed this whole clause in roman and not Gothic type, the equivalent of the later convention of italics. They did this apparently to indicate textual doubtfulness; indeed, again, the entire clause is missing from Stephanus.67

Of course, this category of difference exists between the TRs and the CTs, too. The first entire clause that is present in Scrivener but not in the NA28 is Matthew 17:21: “Howbeit this kind goeth not out but by prayer and fasting.” And, rather significantly, 1 John 5:7–8—the Comma Johanneum—is also present in Scrivener but not in the NA28. If “omission” equals denial (it does not), then the critical text is doctrinally faulty at 1 John 5:7–8; but Stephanus’ TR is also then doctrinally faulty at 1 John 2:23. The point here, however, is that “missing clauses” is a kind of difference that occurs between TRs, not just between the TRs and the CTs.

Missing Sections

The one category of difference which is not found between TRs but is found between the TR and CT traditions consists of two passages: Mark 16:9–20 and John 7:53–8:11. All forms of KJV-Onlyism, whenever they discuss textual variants, invariably mention these two sections. These two passages constitute the most serious threat to the critical text view: why indeed would God allow uninspired text to be received by his church for so long?

Evidence suggests, however, that God may have left them out for an equally long period in the ancient past. And even during the period of transmission history in which the story appeared, there are “three primary lines of transmission” for the story—three different versions. Maurice Robinson, prominent Majority Text advocate, says that “each of these three lines—termed by von Soden μ5, μ6, and μ7—retains a near-equal level of support.”68

An argument from what God’s people in fact possessed through time does not indicate which version of the Pericope Adulterae ought to be accepted. For the purposes of this article and this argument, however, it must be acknowledged that John 7:53–8:11 and Mark 16:9–20 make up the lone serious, substantive kind of difference that exists between the two textual traditions.69

Contradictions

Most seriously, there are two places in the New Testament in which the two TRs under examination actually contradict one another. This does not mean that one teaches a false doctrine and another the true, only that both cannot preserve the correct reading. James 2:18 is the first:

| Stephanus | Scrivener |

| ἀλλʼ ἐρεῖ τις, Σὺ πίστιν ἔχεις, κἀγὼ ἔργα ἔχω· δεῖξόν μοι τὴν πίστιν σου ἐκ τῶν ἔργων σου, κἀγώ δείξω σοι ἐκ τῶν ἔργων μου τὴν πίστιν μου. | ἀλλʼ ἐρεῖ τις, Σὺ πίστιν ἔχεις, κἀγὼ ἔργα ἔχω· δεῖξόν μοι τὴν πίστιν σου χωρὶς τῶν ἔργων σου, κἀγώ δείξω σοι ἐκ τῶν ἔργων μου τὴν πίστιν μου. |

| But someone will say, “You have faith, and I have works.” Show me your faith by your works, and I will shew you my faith by my works. | But someone will say, “You have faith, and I have works.” Show me your faith apart from your works, and I will shew you my faith by my works. |

In one clause within this verse, Stephanus (followed by the Bishop’s Bible, which the KJV translators self-consciously chose to go against) has James saying the opposite of what Scrivener (along with the critical text) has him saying. The overall point is the same: works must accompany faith, or it is no true faith. But the rhetorical strategy is markedly different. James is either directly contradicting his imagined interlocutor (as in Stephanus) or subtly, perhaps even sarcastically, challenging his non sequitur (as in Scrivener). As with the examples in the previous category, a choice must be made by any translator of “the TR.”

Revelation 11:2 provides the second of two very simple contradictions between the two TRs. Is John told not to measure the court “inside the temple” (ἔσωθεν, Stephanus) or “outside the temple” (ἔξωθεν, Scrivener and NA28)? Textual critics and translators must choose.

This category of difference occurs between the TR and CT, too. One of the most famous examples is the variant in John 7:8, in which the NA28 has Jesus saying, “I am not going up to this feast.” He does in fact go to the feast, as John later describes—which makes 7:8 awkward, to say the least. Scrivener’s TR has Jesus saying, “I am not going up yet (οὔπω) to this feast.”

Conclusion

Many KJV-Only Bible college professors have personally told me that they are not, in fact, “KJV Only” but “Textus Receptus Only.” They have told me, “The text is the issue.” CB proponents have said the same thing. I suspect that TR defenders, when pressed by a very simple argument like that of this paper, will be willing to clarify in good faith. They will say, “It is Scrivener’s TR that is the perfectly preserved Word of God, not Stephanus’ TR.” I suspect they will appeal as their leading writers have done to the providential use of Scrivener’s TR, especially in the King James Version. They may, as a result of arguments like those in this paper, start adding to their doctrinal statements; instead of saying (as countless KJV-Only churches and institutions now do) that they believe in “the Textus Receptus,” they will clarify that they believe in “F.H.A. Scrivener’s 1881 edition of the Textus Receptus.”

But if they do so, they will prove a bigger point that opponents of KJV-Onlyism have repeatedly made: KJV-Onlyism in all its forms, even when it confesses primary allegiance to “the” Textus Receptus, is still just that: KJV-Onlyism. Because what is Scrivener’s TR except a record of the textual critical decisions of the KJV translators?70 As an arcane scholarly tool, Scrivener’s text is very useful. But professing faith in its perfect preservation still makes the KJV, and not the apostles and prophets, the ultimate standard for Christian faith—now not just in the realm of English renderings but in that of textual critical decisions also.

Until all KJV-Only Christians stop professing allegiance to “the TR” and instead choose one TR, they are in principle accepting precisely the same kinds of textual variation that occur between the TR and the CT, with the exception of the two big chunks: John 7:53–8:11 and Mark 16:9–20.

Would the KJV translators be happy with this situation? Did they intend for their work to be the One Ring to Rule not just all translations but all editions of the Greek New Testament? Clearly not. What they said about translation in their preface surely they would say, too, about their textual-critical judgments (which do not even merit mention in their preface): “What euer was perfect vnder the Sunne, where Apoſtles or Apoſtolike men, that is, men indued with an extraordinary meaſure of Gods ſpirit, and priuiledged with the priuiledge of infallibilitie, had not their hand?”71

The KJV translators did not claim perfection for their work. They made excellent judgments, but they were human judgments. They did not claim the mantle of Bezalel and Oholiab. The Bible does not promise perfect Bible translations—or perfect textual criticism.

The wealth of widely available information about textual criticism of the Greek New Testament—from the NTVMR to (now) multiple textual commentaries and different textual apparatuses—has had a paradoxical effect among some Christian believers. It has actually decreased their trust in the reliability of the critical text tradition.72 Many have sought the apparently greater stability, simplicity, and objectivity of a Majority Text view—or the apparently full certainty and purity of a Textus-Receptus-Only view. And now that certain embarrassing failures and rhetorical excesses of the KJV-Only movement have discredited KJV-Onlyism in the last half century (e.g., Ruckman and Riplinger), contemporary disciples of Hills and Letis have arisen to defend the TR and claim a “confessional” bibliology. But the certainty each group seeks is simply not to be had without some kind of special revelation—or special pleading.

After years of attention given to KJV-Onlyism, it is my opinion that all of its major camps are accepting one presupposition that is driving all of their work: inspiration demands perfect preservation.73

In my opinion, this presupposition is not illogical. It is a plausible read of the jot-and-tittle promise of Matthew 5:18. But when one looks into those jots and tittles, perfect preservation is simply, demonstrably, not what God has given us. So he must not have meant to promise it. Matthew 5:18 must be about the efficacy of God’s words instead. Indeed, the contrast Jesus draws is between the persistence of every-jot-and-tittle and people disobeying, not losing or altering, God’s law (Matt 5:19–20). But every KJV/TR defender—empirically speaking, the two defenses invariably go together—who cites the promise of every-jot-and-tittle preservation is setting up an absolute standard: if one jot or tittle is either not preserved or not identifiable with certainty in its proper location, the position falls. In order for TR defenses to work, and for the rhetoric of “certainty” and “purity” that they use to be true rather than false, we cannot only possess all the jots and tittles. We must also know precisely and with certainty what and where each one of them is, and precisely and with certainty which ones do not count among the 144,000. An appeal to perfect preservation of “the TR” fails by this standard. Which TR is perfect, and how do we know? And if a TR defender who wishes to avoid special pleading says, “All the jots and tittles are preserved—in the totality of the good manuscripts”; that is precisely the position of the majority of evangelical biblical scholars.

The basic argument of this paper, then, is meant to build a bridge between TR defenders and that majority evangelical position. It is meant, to use another image, to reveal that they—we—are in the same boat. The Lord in his good providence has not given any Christian warrant to claim exhaustive and perfect certainty in our textual criticism of the New Testament. TR defenders must stop claiming to have a “pure” and “absolute” text; that claim is, quite simply, causing brothers and sisters to divide unnecessarily.

If I can successfully show a TR/KJV defender that TR editions feature exactly the same kinds of variants as those that occur between the CT and TR—if I can show that our views differ in degree and not in kind—I can perhaps make a small dent in the amount of divisive internet grandstanding in the world, and save a layperson the difficulty of being told by well-meaning brothers that they must call other Christians’ Bibles “corrupt.” What could be more divisive than telling people who cannot read Greek or Hebrew—and therefore lack most of the capacity necessary to check out the issue for themselves—to disdain each other’s Bibles?

- Dr. Ward is an academic editor for Lexham Press, and the author of Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2018).[↩]

- Here is an example from Bible teacher John T. Yates of the Faith Bible Institute, whose program is used in many KJV-Only churches: “The debate between the Minority and Majority texts [is] important to the Christian. Every Word of God…is of eternal importance and must be established with all certainty” (Faith Bible Institute Commentary Series, vol. 1, book 3, The Doctrine of God the Trinity & The Doctrine of the Bible [Monroe, LA: Faith Bible Institute Press, 2018], 223). More examples follow in this first section of the paper.[↩]

- There is no official list of Textus Receptus editions and no independent arbiter of what counts as one; perhaps a Catholic edition indeed does not count. But it meets the two criteria which seem to cause other editions of the Greek New Testament to be treated as TRs: (1) it was printed whole on a press, (2) it came from well before the critical text era, and (3) it used Majority/Byzantine mss.[↩]

- E. F. Hills, Believing Bible Study (Des Moines, IA: Christian Research Press, 2017), Kindle loc. 6484.[↩]

- Jan Krans presents a careful accounting of those editions, with links to full-text scans at Bibliotheque de Geneve, at the Amsterdam Centre for New Testament Studies blog. See http://vuntblog.blogspot.com/2012/11/bezas-new-testament-editions-online.html, accessed 12 February 2020. Editors after Beza’s death produced a 1611 edition of his text in which they altered his conjectural emendation in Rev 16:5, a reading that appears in no available Greek manuscripts and was nonetheless followed by the KJV translators (https://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/content/pageview/2026240), back to what is now the standard reading in critical texts such as the Nestle-Aland 28 (https://www.e-rara.ch/gep_r/content/pageview/16734016).[↩]

- The wording of the famous sentence from which the name Textus Receptus derives is very interesting: “Textum ergo habes, nunc ab omnibus receptum: in quo nihil immutatum aut corruptum damus”—“You have, therefore, the text which is now received by all, in which we give [you] nothing altered or corrupted.” Naturally, it has been of interest to New Testament readers from time immemorial to have “nothing altered or corrupted.” But it was extremely difficult in the days before computerized diff-checkers to establish the truth of this claim. And the Elzevirs’ bold claim assumes a standard that has come under very reasonable question since their time.[↩]

- Scrivener, as reported (and slightly corrected) by Hoskier, did collate the two TRs that prevailed in use in England (Stephanus, 1550) and the continent (Elzevirs, 1624) in his day. Excluding breathing marks and accents, he found 286 differences between the two. Hoskier, at each place where the Stephanus TR and the Elzevir TR differed, showed the reading of multiple other TR editions (Herman Hoskier, A Full Account and Collation of the Greek Cursive Codex Evangelium 604, Appendix B, “A Reprint with Corrections of Scrivener’s List of Differences Between the Editions of Stephen 1550 and Elzevir 1624” [London: David Nutt, 1880]). Hoskier dedicated his book to Dean Burgon.[↩]

- See “Appendix E: The Greek Text adopted by the Translators of the Authorized Version of the New Testament,” in The Cambridge Paragraph Bible of the Authorized English Version (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1873), c–civ.[↩]

- The edition that is universally used is that provided by the Trinitarian Bible Society.[↩]

- Texti ergo habes, nunc ab omnibus recepti[↩]

- The mainstream KJV-Only movement is probably best defined by the constituencies of the largest KJV-Only educational institutions such as Ambassador Baptist College, Crown College of the Bible, West Coast Baptist College, Pensacola Christian College, Hyles-Anderson College, Faithway Baptist College, and others. Other institutions in the same general orbit include mission boards, tract publishing ministries, and smaller Bible colleges run out of local churches. James White offers a helpful five-fold taxonomy of KJV-Only views in The King James Only Controversy: Can You Trust Modern Translation? (Minneapolis: Bethany House, 2009), 23–28.[↩]

- This writer looks compulsively at bibliology statements on KJV-Only church websites, and after looking at hundreds of such statements, has discovered not one that acknowledges differences among TRs, or specifies which TR they believe to be perfectly “preserved.” In other words, they all assume that “the TR” is one text.[↩]

- “Although God inspired the authors of the Bible to produce a divinely superintended record, he has committed the reproduction and the preservation of the text to the vagaries of human history; and the establishment of a trustworthy text is the labor of a scientific scholarship” (George Eldon Ladd, The New Testament and Criticism [Grand Rapid: Eerdmans, 1967], 80).[↩]

- A More Sure Word: Which Bible Can You Trust? (Lancaster, CA: Striving Together Publications, 2008), 76.[↩]

- Certainty of the Words: Biblical Principles of Textual Criticism (Shelby, NC: Surrett Family Publications, 2013), 13.[↩]

- Ibid., 41.[↩]

- “Understanding the Development of the Textus Receptus and Its Relationship to the King James Version,” unpublished paper, n. d., available at https://www.bpsglobal.org/ uploads/2/9/3/0/29302395/understanding_the_development_of_the_textus_receptus.pdf.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Ibid., 4. See also the comment of the mainstream KJV-Only book edited by Kent Brandenburg, Thou Shalt Keep Them: A Biblical Theology of the Perfect Preservation of Scripture (El Sobrante, CA: Pillar & Ground, 2003): “The editions of Scrivener printed in 1881 and thereafter represent the exact Greek text underlying the King James Version of the Bible and the preserved autographa” (Kindle loc. 156).[↩]

- Such a descriptor would have surprised Scrivener, who had a rather different impression of his stated task. Scrivener had no intention of producing the once-for-all, perfectly pure Greek New Testament. Scrivener was on the committee that produced the Revised Version, which used Westcott-Hort’s Greek text (though it also felt free to depart from it at points). His design in producing his edition of the TR was very practical: “The special design of this volume is to place clearly before the reader the variations from the Greek text represented by the Authorised Version of the New Testament which have been embodied in the Revised Version. One of the Rules laid down for the guidance of the Revisers by a Committee appointed by the Convocation of Canterbury was to the effect ‘that, when the Text adopted differs from that from which the Authorised Version was made, the alteration be indicated in the margin.’ As it was found that a literal observance of this direction would often crowd and obscure the margin of the Revised Version, the Revisers judged that its purpose might be better carried out in another manner. They therefore communicated to the Oxford and Cambridge University Presses a full and carefully corrected list of the readings adopted which are at variance with the readings ‘presumed to underlie the Authorised Version,’ in order that they might be published independently in some shape or other. The University Presses have accordingly undertaken to print them in connexion with complete Greek texts of the New Testament.” In other words, Scrivener’s TR was meant to be a practical tool making it possible to see where the Westcott-Hort text differed from the text underlying the KJV. This was difficult to do before Scrivener, because no GNT existed that perfectly reflected the textual-critical decisions of the KJV translators (F. H. A. Scrivener, The New Testament in Greek [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1881], xxiii).[↩]

- One exception is a statement by Thomas Ross which specifies that the New Testament has been “perfectly preserved in the common printed Received Text, the Scrivener edition underlying the Authorized Version,” https://faithsaves.net/ inspiration-preservation-scripture/, accessed August 28, 2019. Much more common among mainstream KJV-Only institutions is the wording in Crown College’s doctrinal statement: “The Masoretic Text of the Old Testament and the Received Text of the New Testament (Textus Receptus) are those texts of the original languages we use,” available at https://thecrowncollege.edu/about-crown/what-we-believe/, accessed 28 August 2019.[↩]

- I have never seen defenders of the KJV acknowledge that other TRs were used in other KJV-equivalents in European languages. In the TR the Dutch translators of the 1636 Statenvertaling used, for example, the wise men “found” (vonden, translating εὺρίσκω) the child Jesus (the TR-based Portuguese Bible does the same). The KJV, following a different TR, says they “saw” (ὸράω) him. In the Dutch Bible, Jesus warns against Beelzebul (Matt 10:25), not Beelzebub as in the KJV. Perhaps this is just a spelling difference, maybe not; it is not clear. This is clear: the jots and tittles are different here between the two TRs. In the Dutch version of 1 Tim 1:2, Paul wishes grace, mercy, and peace on Timothy from “Christus Jezus,” reflecting a different TR text. In the KJV it is “Jesus Christ.” The Dutch used a TR that repeats “their robes” twice in Rev 7:14; the KJV used a TR that has it once. “Staff” in Matt 10:10 is singular in the Dutch translators’ TR and plural (“staffs”) in the KJV translators’ TR. There is a formal contradiction at James 2:18 between the TR underlying the Dutch version and the one underlying the KJV. English-speaking believers over the centuries have read, “Show me your faith without [apart from; χωρις] your works”; Dutch-speaking believers have read “Show me your faith by [through; εκ] your works.” Perhaps God did not intend for providential use to be the means by which textual criticism is accomplished, for it does not speak with one voice.[↩]

- More scholarly than mainstream KJV-Onlyism, though there is noticeable overlap between the two groups: KJV-Onlyism regularly appeals to the same writers who are respected and used among CB, but KJV-Onlyism struggles to produce anything approaching their quality.[↩]

- Riddle is a Reformed Baptist pastor who holds a Ph.D. from Union Theological Seminary in Virginia.[↩]

- Truelove is a Reformed Baptist pastor and moderator of a popular and active Facebook group, “Text and Canon.” He assisted in the release of a new edition of Hills’s The King James Version Defended, one that used Hills’s original title and (rather oddly) interpolates contemporary editorial comments from Hills’s daughter. See Text and Time: A Reformed Approach to New Testament Textual Criticism, 6th ed. (Des Moines, IA: Christian Research Press, 2018).[↩]

- Milne, recently deceased, was a pastor in New Zealand who has published a monograph on Reformed bibliology with Paternoster. See The Westminster Confession of Faith and the Cessation of Special Revelation: The Majority Puritan Viewpoint on Whether Extra-Biblical Prophecy Is Still Possible (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock), 2008. # [27]See, for example, Jeffrey Riddle’s use of Joel Beeke’s “13 Practical Reasons to Retain the KJV,” available at http://www.jeffriddle.net/2009/07/joel-beeke-on-practical-reasons-for.html; see also Truelove’s satirical post, “Learn Cuneiform to Read the KJV!” available at https://roberttruelove.com/learn-cuneiform-to-read-the-kjv/.[↩]

- FOOTNOTE 27 NOT FOUND[↩]

- Taylor DeSoto and Dane Jöhannsson, young leaders within the Confessional Bibliology world, in a discussion with Peter Gurry of the Text & Canon Institute, used these words to describe the TR: “pure,” “perfect,” “certain,” “absolute,” “stable,” “settled,” “not changing,” “completed,” “agreed upon.” DeSoto said, “There’s not a single place where I don’t know what the text says.” He argued that if there is uncertainty anywhere, there is uncertainty everywhere (“Agros Church Special: Pastor Taylor DeSoto and Dr. Peter Gurry,” available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-QAvGaCinIs).[↩]

- The Westminster Confession of Faith (Carlisle, PA: The Banner of Truth Trust, 2018).[↩]

- Or, often, the “traditional text” or “ecclesiastical text” or “received text.”[↩]

- Note also the WCF’s use of Matthew 5:18 as a prooftext: “Truly, I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the Law until all is accomplished” (Matthew 5:18 ESV).[↩]

- See Collin Hansen, Young, Restless, Reformed: A Journalist’s Journey with the New Calvinists (Wheaton: Crossway, 2008).[↩]

- A recent graduate of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary joins a current student at Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary as proprietors of ConfessionalBibliology.com.[↩]

- The Works of John Owen, ed. William H. Goold, vol. 16 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, n.d.), 345ff.[↩]

- Ibid., 353. Letis cites these very words in his The Ecclesiastical Text (Kindle loc. 980).[↩]

- “Reformed Confessions of Faith and the Traditional Text,” February 15, 2018, available at https://www.roberttruelove.com/reformed-confessions-of-faith-and-the-traditional-text/.[↩]

- 3rd edition (Brighton, IA: Just and Sinner Publications, 2018), chap. 2, sec. IIIA.[↩]

- Letis, Ecclesiastical Text, Kindle loc. 303. This rhetorical move is precisely parallel to that used by mainstream KJV-Onlyists, who commonly argue that inspiration of the originals does contemporary believers no good because the originals are lost.[↩]

- The two leading proponents of Confessional Bibliology both address the “Which TR?” question—and both fail to give a specific and direct answer (Jeff Riddle, “Responding to the ‘Which TR?’ Objection,” Stylos Blog, November 20, 2019, available at http://www.jeffriddle.net/2019/11/wm-140-responding-to-which-tr-objection.html; Robert Truelove, “Which Textus Receptus?” RobertTruelove.com, n.d., available at https://www.roberttruelove.com/which-textus-receptus/, accessed 17 February 2020). Various influential defenders of the TR have pointed to Scrivener (Riddle, Truelove, the Trinitarian Bible Society, and many others), Stephanus (Douglas Wilson), and Beza (Chuck Surrett, who later pointed to Scrivener instead), as the best—or, in some cases, the perfect—exemplar of the TR tradition.[↩]

- Hills, Believing Bible Study, Kindle loc. 6767.[↩]

- Hills, Text and Time, Kindle loc. 5510. Hills defines the “Traditional Text” to include the editions of Stephanus (1550) and Elzevir (1633) and “the vast majority of the Greek New Testament manuscripts.” He also identifies the term with “the Textus Receptus” and the “Received Text,” and he says that “critics have called it the Byzantine text” (ibid., Kindle loc. 2790).[↩]

- Hills, Believing Bible Study, Kindle loc. 6818. See above, at note 21. To this writer’s knowledge, no CB proponents have explained why the KJV and not the Dutch, French, German, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, or other early European-language Bibles should be considered to provide the divine answer to the question, “Which TR?”[↩]

- Hills, Believing Bible Study, Kindle loc. 6484. Hills hedges here—Erasmus “may have been guided,” he says. But his argument can only work if he does not hedge. According to the rest of what Hills writes, any choice made by Erasmus that ended up in the KJV must have been guided by God.[↩]

- See also εσομεν vs. οσιος in Rev 16:5—a place where the KJV translators self-consciously opted for a conjectural emendation in Beza, one that has no support in the manuscript tradition—a choice they made against the combined testimony of Stephanus, Tyndale, and the Bishop’s Bible, which all have the reading adopted universally elsewhere.[↩]

- Hills, Believing Bible Study, Kindle loc. 6629.[↩]

- Hills, Text and Time, Kindle loc. 5386.[↩]

- Robert Truelove, “Why are you using the King James Version? Are you KJVO?” February 24, 2020, https://roberttruelove.com/why-are-you-using-the-king-james-version-are-you-kjvo/. The proprietor of textusreceptusbibles.com, a frequent participant in online discussions over Confessional Bibliology and Received Text advocacy, has compared being called “KJV-Only” to being called the N-word.[↩]

- “Theodore Letis,” Evangelical Textual Criticism, January 26, 2006, available at http://evangelicaltextualcriticism.blogspot.com/2006/01/theodore-letis.html.[↩]

- Hills: “It must be that down through the centuries God has exercised a special, providential control over the copying of the Scriptures and the preservation and use of the copies, so that trustworthy representatives of the original text have been available to God’s people in every age” (Text and Time, Kindle loc. 273). Milne, in his book, goes further in his rhetoric, pitting the “absolute purity” of the TR against the “partial” or “substantial” purity which is all critical text proponents such as Warfield can claim (Has the Bible Been Kept Pure? The Westminster Confession of Faith and the Providential Preservation of Scripture [Seattle: Amazon Digital Services, 2017], 24). Milne argues that “the Westminster divines…believed unequivocally that they possessed the entire autographic Scripture word for word” (ibid., 46). He says, “It is my prayer that the church will rediscover the absolute certainty, which Calvin and those who followed him held—that we have the sealed oracles of God, the same divine words available to the Apostles and the Reformers and preserved for us down to our own day” (ibid., 67). He says further, “It is impossible to have spiritual stability without an immutable foundation” (ibid., 192). And he concludes his book with the answer to its titular question: “The Reformed orthodox of the first and second Reformations believed that they possessed the complete Word of God dictated by the Holy Spirit in its textual purity” (ibid., 305). Milne does acknowledge along the way that “there are scribal errors in minor matters in the text which do not compromise the teaching of the Bible in any way” (ibid., 304), but this is difficult to square with his repeated invocations of immutable purity and of absolute certainty.[↩]

- Hills writes, “There are two methods of New Testament textual criticism, the consistently Christian method and the naturalistic method” (Text and Time, Kindle loc. 297). “There are many scholars today who claim to be orthodox Christians and yet insist that the New Testament text ought not to be studied from the believing point of view but from a neutral point of view” (Kindle loc. 1752).[↩]

- This is the latest front in the battle over CB. A recent CB conference featuring Robert Truelove and Jeffrey Riddle is called “The Text and Canon Conference.” Riddle has written of this topic, “The concept of biblical canon includes not only the authoritative books which make up the Bible but also the authoritative text of those books.” “Review of Stanley Porter, How We Got the New Testament: Transmission, Translation,” Puritan Reformed Journal 10 (January 2018): 52. Riddle has also complained elsewhere that via the majority evangelical view of textual criticism, “believers deliver custody of their Scriptures to the academy.” “Review of Stanley Porter, How We Got the New Testament: Transmission, Translation,” Puritan Reformed Journal 9 (January 2017): 310. In both KJV-Only and CB views, the church is often considered the pillar and ground of textual critical choices. In this writer’s opinion, CB proponents will continue to use for textual criticism the arguments Michael Kruger has made for a self-authenticating canon (Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books [Wheaton: Crossway, 2012]). Opponents to CB’s view will continue to point out that a great portion of the living church is not using the TR today, so that even if textual critical decisions are best made by looking for which variants the church has received, this still points toward the critical text. The two groups will likely never resolve this division.[↩]

- Hills, Believing Bible Study, Kindle loc. 6484.[↩]

- One of the most influential leaders of Confessional Bibliology, Jeffrey Riddle, characterized the two texts in the following way: “The difference between the KJV and the ESV, for example, is not just a debate about updating of language but of a completely different underlying text” (“A Review of Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible,” The Bible League Quarterly 479 [Oct–Dec 2019]: 30).[↩]

- John Owen, The Works of John Owen, ed. William H. Goold, vol. 16 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, n.d.), 364.[↩]

- For the reader’s convenience and for the help of students, all of the variants between Scrivener and Stephanus listed below can be viewed at https://kjvparallelbible.org/kinds-of-differences-between-trs. A further list of differences among TR editions—one gathered by Scrivener himself—can be viewed at https://kjvparallelbible.org/which-tr-stephanus-vs-beza/.[↩]

- Most interpreters think they are alternate spellings of the same name. BDAG defines Beelzebub as “lord of flies” and says, “Whether בַּעַל זְבוּל [Beelzebul] (=lord of filth?) represents an intentional change or merely careless pronunciation cannot be determined with certainty” (173).[↩]

- Author’s translation.[↩]

- Trinitarian Bible Society, “Statement of Doctrine of Holy Scripture,” available at https://www.tbsbibles.org/page/DoctrineofScripture, accessed 15 October 2018. Interestingly, the TBS bibliology statement opens with explicit appeal to WCF 1.8. Notice that even within a statement in which the TBS acknowledges that TR editions differ, they still refer to a singular “Greek Received Text.”[↩]

- A diligent MA student could possibly come up with a reasonably objective answer to this question. It is my opinion that very few would be left. Regrettably, work for this paper had to stop at some point.[↩]

- I have examined every one of this latter set of differences for a project available at KJVParallelBible.org.[↩]

- Contemporary English translations generally feel free to turn historical presents into pasts, which sound more natural in English, so this particular difference is often invisible to English readers. See Mark Ward, “How to Search Connections between Greek and English Bibles,” Logos Talk Blog, June 15, 2017, available at https://blog.logos.com/2017/06/search-connections-greek-english-bibles.[↩]

- Garnet Milne writes, “Modern textual criticism is not purely scientific, relying on inviolable and self-evident rules or laws. There is patently a significant subjective component involved, so that Warfield can have certain passages which require conjectural emendation and Westcott and Hort, using the same critical principles, have many other and different passages in need of some guesswork” (Has the Bible Been Kept Pure? 36).[↩]

- The fascinating 41st volume of the Collected Works of Erasmus (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019) has recently been released, and editor Robert D. Sider commented, “There is no indication that Erasmus intended to publish a ‘critical text’ of the Greek New Testament” (43). His goal was to amend the Vulgate. Erasmus himself wrote of his Novum Instrumentum Omne, “I had undertaken to translate the Greek manuscripts, not to correct them, and in fact, in not a few places I prefer the Latin translation to the reading in the Greek” (44 n. 194). This is so true that, infamously, and as he himself admitted, he back-translated the last page of Revelation into Greek from Latin (46).[↩]

- The Bishop’s Bible reads “shut up,” which ironically means something like “silenced” in today’s English but in 1568 was a somewhat interpretive rendering of σφραγίσεται.[↩]

- Possibly, a scribe read the text without spaces—ΙΝΑΜΗΥΠΟΚΡΙΣΙΝΠΕΣΗΤΕ— and misjudged one of the word boundaries, failing to divide ΥΠΟΚΡΙΣΙΝ into υπο κρισιν and winding up with “hypocrisy” rather than “under condemnation.” This word division left some scribe(s) with a difficulty: the sentence is clearly missing a word (“in order that they might not fall hypocrisy”). And the only viable candidate is εις (“in order that they might not fall into hypocrisy). So εις was dutifully added in. The scribe who did this surely thought he was correcting someone else’s mistake; he did not realize he was adding his own. Anyone who sees ΙΝΑΜΗΕΙΣΥΠΟΚΡΙΣΙΝΠΕΣΗΤΕ will know immediately that the key word is hypocrisy; otherwise there would be a meaningless doubling up of prepositions (ΕΙΣΥΠΟ).[↩]

- Two more matters of interest to modern-day scriveners: (1) In Galatians 3:8, there is a clear but minor difference between ευλογηθησονται (Scrivener) and ενευλογηθησονται (Stephanus). This variant is significant, however, because the modern critical text goes with Stephanus against Scrivener. Indeed, in many places where Stephanus and Scrivener disagree, the critical text has the same reading as Stephanus. (2) In Hebrews 11:14, Abel “still speaks” either in the middle voice (λαλειται, Stephanus) or the active (λαλει, Scrivener). There is no difference in meaning here, nor in translation. But there is still something interesting to note: the KJV translators go against the majority of manuscripts to select λαλει. In fact, they agree with the modern critical text here against that majority.[↩]