Discontinuity to Continuity: A Survey of Dispensational and Covenantal Theologies, by Benjamin L. Merkle. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2020. 288 pp. $25.99.

Not long ago, one was presented with a binary choice of theological systems—dispensationalism or covenant theology. Over the last few decades, however, the number of systems has multiplied. While it is true that each system still falls on either the covenantal or the dispensational side (primarily on the question of the future of national Israel), the details of each system have become more nuanced and complex. For this reason, Benjamin Merkle’s new book Discontinuity to Continuity is a needed primer on the current state of theological systems.

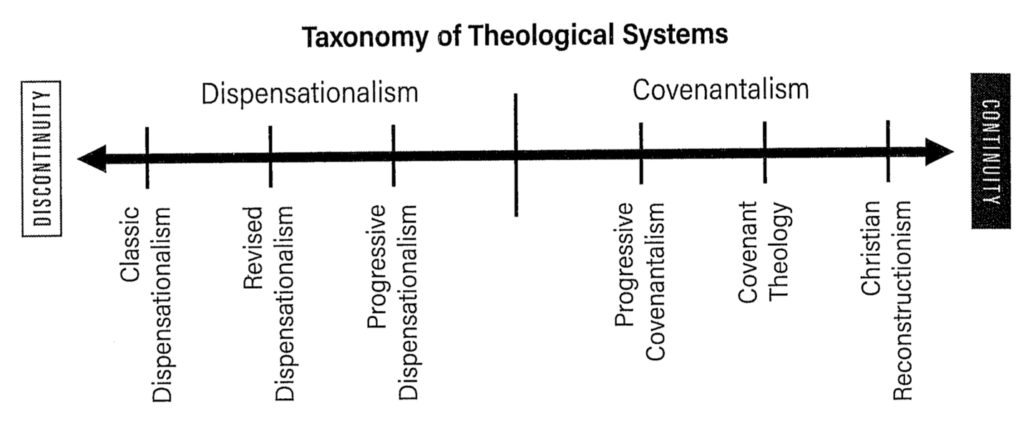

The name of the book highlights the direction of the volume. Beginning with theological systems that stress the discontinuity of Scripture, Merkle then moves step by step towards theological systems that stress continuity. The following image, which is used throughout the text, displays the six theological systems organized according to their place on the scale of continuity.

One of the greatest strengths of the volume is its meticulous organization. Merkle asks the same four questions, along with sub-questions, of each theological system. This makes it easy to compare the individual systems. The following outline indicates the questions and sub-questions asked of each system:

1. What is the Basic Hermeneutic?

a. Literal or Symbolic?

b. What is the Proper Role of Typology?

c. How should one Interpret Old Testament Restoration Prophecies to Israel?

i. Amos 9:11–15

ii. Acts 15:14–18

2. What is the Relationship Between the Covenants?

a. Conditional or Unconditional?

b. How are Old Testament Saints Saved?

c. How does one Apply the Law Today?

3. What is the Relationship Between Israel and the Church?

a. Replacement, Fulfillment, Distinct?

b. How should one Interpret Romans 11:26 and Galatians 6:16?

4. What is the Kingdom of God?

a. How is it inaugurated?

b. When is it Consummated?

To answer these questions, Merkle selected three conversation partners within each system. This allowed him to limit his scope, while also highlighting the work of the most significant interpreters within each of the groups. And since Merkle asks just the right questions, he is able to clearly highlight the distinctives of each system.

Merkle concludes each chapter with an “assessment,” which is designed to “evaluate the potential strengths and weaknesses of each theological system” (49). Addressing the strengths and weaknesses of these systems is hard to do while seeking to remain objective. And it is here, more than anywhere else, that one will find Merkle’s own views being expressed. For example, he notes that a strength of revised dispensationalism is that it sees “more continuity between the covenants, especially the idea that the new covenant relates to the church” (75). But this is only a strength if you find that to be a good thing, which some dispensationalists do not!

On the whole however, Merkle does a splendid job working towards objectivity in his presentation. Proponents of each position would likely read their respective chapter and agree that Merkle captured the essence of their view.

A few comments should be made about the selection of theological systems. First, Merkle recognizes that his list does not exhaust all of the theological systems. In the conclusion, he includes a brief consideration of how Lutheran thought, with its law-grace dualism, might fit into the broader discussion. Additionally, in the chapter on Progressive Covenantalism, Merkle included a number of footnotes showing how New Covenantalism understood the same issues.

Second, Merkle could have more clearly shown that there is diversity within revised dispensationalism. The stream he chose is the more popular Dallas stream, but there is a less known, though significantly influential stream from Grace Theological Seminary. Alva McClain and his views on the kingdom deserve, at least, a place in the footnotes of that chapter.

Third, the inclusion of the far left (classical dispensationalism) and far right (Christian Reconstructionism) systems was imbalanced. In short, Classical Dispensationalism was an immature, developing form of dispensational thought, while Christian Reconstructionism is a developed, hyper-form of covenantal thought. Accordingly, a fair comparison to Classical Dispensationalism would be a seventeenth-century form of covenantalism, as both are immature forms that are held by almost no one today. In regard to Christian Reconstruction, a fair comparison would be hyper-dispensationalism, as both of these movements take their systems to the extreme and have very small followings.

Despite these slight criticisms, this is a good book. It is fair and balanced, especially in the description sections, though less so in the analysis sections. Merkle wrote that he hoped the work would help readers know their own position, appreciate the positions of others, be humble in their own view, and gain a love for Scripture (1–4). The greatest recommendation I can give is to say that I think the book will succeed in all four areas.

![Discontinuity[1]](https://dbts.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Discontinuity1.jpg)