Discovering Dispensationalism

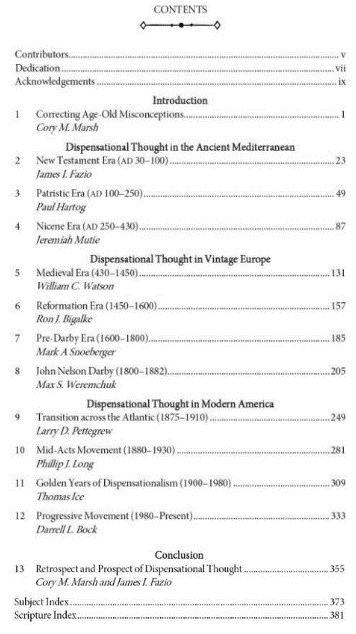

Just a few weeks ago, SCS Press released a new book that will likely be of interest to many of our readers. Editors Cory Marsh and James Fazio, both professors at Southern California Seminary, have brought together a group of scholars from a variety of educational contexts to discuss an often-controversial issue, namely, the history of dispensationalism.

In the past, several authors (e.g., William Watson) have pushed back against the claim that dispensationalism was created almost ex nihilo by John Nelson Darby in the 1830s. What is unique about Discovering Dispensationalism is that the contributors seek to highlight key dispensational principles that can be found in nearly every era of church history. This aim is aptly summarized in the book’s subtitle: Tracing the Development of Dispensational Thought from the First to the Twenty-First Century.

A book of this type, with some dozen contributors, may not have a tightly argued thesis, but it does put forward a significant and somewhat controversial claim, namely, that important elements of dispensational thought can be found not just in the past two hundred years or so but throughout church history. William Watson’s essay illustrates this claim with regard to his time period:

This chapter will show that ideas now considered distinctly dispensational were present in the medieval period—contrary to those who assert that dispensational patterns of belief are a modern innovation. Specifically, this chapter will focus on antiquitous positions reflecting dispensational thought from both the Late Antiquity (5th–9th) and Late Medieval (10th–15th) centuries. Proto-dispensational elements found in these periods include: sacred history being divided into periods in which God deals with humanity in different ways; a literal interpretation of Scripture—especially prophetic passages—rather than spiritualizing of them; belief in a literal future Antichrist; a literal restoration of God’s earthly people to their own land; a literal rapture of God’s heavenly people; a literal period of tribulation immediately preceding Christ’s return; and a literal millennium with Christ ruling on earth with His saints.

pages 131-32

In a similar vein, Mark Snoeberger concludes his chapter on the 17th and 18th centuries by stating,

…the major features of modern dispensationalism are not without historical precedent: literal, that is, ethnic interpretations of OT promises to Israel; expectation of eschatological restoration of the Jews—not only spiritual, but also political and geographical; and the anticipation of Jewish distinctiveness and prominence in the ages to come.

…these views were prominent in the two centuries of Christian history under review, in many cases even majority views in Protestant theology; So widespread were these views, in fact, that one might reasonably argue that the more curious “novelty” of the nineteenth century is not the incorporation of these ideas by dispensationalists, but the total excoriation of these ideas by the Reformed.

page 201

In view of the tendency of modern scholarship to dismiss dispensational scholarship out of hand, it will be interesting to see how this volume is received.

Dispensationalism is a system; i.e. a group of doctrines working together as an integrated whole. The issue of whether disparate components of that system were present before the creation of the system itself seems irrelevant for dating the formation of the system.

I personally don’t think it works that way. A system–at least a system of ideas–consists of a couple of things: a) Recognition of how existing things/ideas relate to each other, and b) using the features of relationship between ideas as arguments to support additional ideas.

So, in the creeds and confessions (especially the later ones), we find not only doctrine directly revealed in this passage or that but also theological reasoning from other doctrines. We find systems at work.

I see a project this one for Dispensationalism as a great idea, because the system is only the principles + the relationships between them. If you show historical validity of the principles, you’re more than half way to supporting the historical validity of the system.

A system is more than the sum of its parts, but not really a whole not more. (Not that there are any perfect systems, either, but we are better with them than without them.)

Two typos: “project *like this one” and “not really a whole *lot more”

The book is well researched and well written.