Why I Won’t Tell My Son That Santa Is Real

*This post was originally published in 2013.

My wife and I are looking forward to enjoying our first Christmas as parents, even if our son is currently more interested in putting wrapping paper in his mouth than in any other part of Christmas. It’s still fun to discuss what traditions we want to establish as a family. One common tradition that we have decided against is pretending that Santa Claus is real. Though there are several practical issues that could come into play—like the logistics of keeping all the presents hidden before bedtime on Christmas Eve so that they could suddenly appear under the tree on Christmas morning, the challenge of explaining how Santa could enter our house with no chimney, or the problem of other kids one day shattering our son’s belief in Santa—there are two larger reasons that led us to our decision

(NOTE: My goal is not to make parents feel guilty for telling their children that Santa is real. It is simply to offer some reasons to reconsider.)

First, there is the problem of pretending. Children have an extraordinary capacity for make believe. Their ability to drink an empty cup of tea, mow grass on the carpet, or have conversations with stuffed animals is a valuable skill. Parents should encourage these imaginative expressions in their children.

But there is a difference between pretending and believing, and children are good at both. When children pretend, everyone is “in” on the pretense. When they believe, they are trusting that someone else is telling them the truth. That’s why Jesus points to the faith of a child when he is explaining the kind of faith necessary for salvation. Their faith is commendable, not because it is foolish, but because it is pure, simple, and wholehearted.

Since children are quick to trust, they will believe almost anything their parents tell them. Without too much trouble, you can get a child to believe that babies are delivered by storks, that if he distorts his face it will freeze, that a magical fairy replaces teeth with money, or that the UM football players hate puppies (something I may or may not be considering telling my son).

Why aren’t adults as quick to believe? Because we’ve learned that people don’t always tell us the truth. We believed what someone else told us only to later discover that they were lying. Often, these lies were told by other people—not our parents. Thus, it is impossible for parents to preserve a child’s readiness to believe. But we can work to point that belief in the right direction while the readiness remains.

For my son, there is nothing I want more than for him to exercise that childlike faith in trusting Jesus. So I want to focus his propensity to believe on the truth of the Bible. Rather than acting as though faith were something to be enjoyed while young and discarded once we mature, I want to communicate to my son that faith is something to be cherished and maintained because it is faith in the truth. And I think that getting my son to believe in Santa would be a hindrance to that effort.

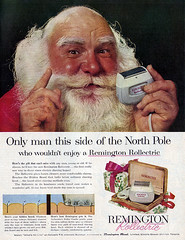

Second, there is the problem of Christmas. Our society exhibits an ever growing emphasis on materialism at Christmas. Even the non-Christian virtues of family, friendship, and goodwill are becoming victim to the all-consuming push for buying and receiving things. The myth of Santa Claus has been seized by retailers to promote this mindset. Rather than representing a self-less person more committed to giving than receiving, Santa has become a kind of magical creature whose primary purpose is to satisfy the wants of little children.

is the problem of Christmas. Our society exhibits an ever growing emphasis on materialism at Christmas. Even the non-Christian virtues of family, friendship, and goodwill are becoming victim to the all-consuming push for buying and receiving things. The myth of Santa Claus has been seized by retailers to promote this mindset. Rather than representing a self-less person more committed to giving than receiving, Santa has become a kind of magical creature whose primary purpose is to satisfy the wants of little children.

I’m not so naïve to think that Christmas can be recaptured in our society so that the focus is on the birth of Christ. But I do want to do what I can to make Christ the focus of Christmas in our family, even while participating in many of the cultural activities surrounding Christmas.

In the next few years, my son will probably not be able to understand who God is or what Jesus accomplished in His life, death, and resurrection. But I hope he will grow to understand that his father loves him and wants to give good things to him. That, in turn, I hope will eventually turn to an understanding of God as a loving Father—imagery often employed in Scripture.

I want my son to focus on Christ at Christmas. And I think that a transition from a loving earthly father who gives gifts (and disciplines) to a loving heavenly Father who gave the ultimate gift will be easier than starting with a focus on an unknown man who lives in the North Pole and visits once a year. Thus, I won’t be telling my son that Santa is real, but I will tell him that his loving father who gives him gifts at Christmas serves an even greater Father who gave the greatest gift at Christmas by sending His Son to be the Savior of the world.

I was surprised to learn this week that couple members of my family (both young pastors) are doing the same. Sound and principled reasoning – good for them and for you.