Does Proverbs Plagiarize from Egyptian Wisdom?

Recently, I came across a Reddit thread with a provocative title: “The Bible’s God-inspired book of Proverbs is plagiarized from the Egyptian Teachings of Amenemope.” The thread was of interest because I had recently finished working through the section that allegedly borrows from The Instruction of Amenemope in my work for a forthcoming Proverbs commentary in the Kerux series by Kregel. Many English versions give their stamp of approval to this supposed borrowing by their translation of Proverbs 22:20: “Have I not written for you thirty sayings of counsel and knowledge?” (ESV). The “thirty sayings” reflects the translators’ decision to emend the Hebrew text to match the thirty chapters of the Egyptian writing. Is this a legitimate translation choice? To answer this question, we begin with a closer look at Amenemope, the possible connections between the two writings, and why I think that the alleged connection is overplayed.

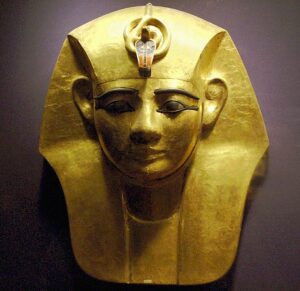

The Origin of Amenemope

In 1888, English Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge acquired the text from an antiquities dealer in Thebes. He did nothing with it, however, until 1922, when he published substantial portions in a French festschrift. Adolf Erman soon posited that the author of Proverbs had used the Egyptian text as a source for much of Proverbs 22:17–24:22. For some time following Erman, this view gained ascendancy, and a majority of critical scholars assumed literary dependence (with the exception of Oesterly [1927], Kevin [1930], Drioton [1957], and most conservative scholars).

In the late twentieth century, however, that consensus began to unravel. John Ruffle dismissed the view that any sort of dependence exists between the works, chalking it up rather to shared cultural norms. G. E. Bryce, basing his work on the earlier continental scholarship of I. Grumach took a middle course by suggesting that both the biblical text and the Egyptian wisdom piece were based on a common earlier text. Diethard Römheld argued a decade after Ruffle, however, that the Proverbs section was based directly and undeniably on Amenemope, surmising that the Hebrew sage had merely infused new piety into the insights of the Egyptian original. So the debate has not completely resolved itself within scholarly circles, although the best evidence appears to be slightly in favor of a limited literary relationship.

The text of Amenemope is preserved in a total of six extant documents, with the most complete version found in the BM 10474 papyrus dating to the seventh century B.C. Based on the formation of several Egyptian hieroglyphs as well as the provenance of the ostracon in an ancient settlement named Deir el-Medina, which was abandoned following the death of Ramesses XI (1099–1069 B.C.), Paul Overland has tentatively dated the document to within the 20th dynasty (1186–1069 B.C.) and, more specifically, to the reign of Ramesses IV (1153–1147 B.C.) (Overland, “Paleographic Dating,” 6).

Comparisons between Proverbs and Amenemope

Critical Bible scholars often work from the premise that Proverbs borrowed from Amenemope. Given the likely origin of Amenemope during the reign of Ramesses IV, the Egyptian scribe Senu copied down the writing at the dictation of the eponymous sage some two centuries before Solomon. While this connection does not entail that Solomon borrowed from the Egyptian source (he has transformed, even in such a scenario, its teaching to a Yahwistic worldview), Solomon could have known of the work from an Egyptian source. Proverbs may, therefore, reflect some themes from Amenemope. Below are a few thematic similarities.

| Proverbs | Instruction of Amenemope |

| Do not rob the poor, because he is poor, or crush the afflicted at the gate. (22:22) | Guard yourself from robbing the poor, from being violent to the weak. (4.4–5) |

| Make no friendship with a man given to anger, nor go with a wrathful man, lest you learn his ways and entangle yourself in a snare. (22:24–25) | Do not associate with the rash man nor approach him for conversation . . . When he makes a statement to snare you and you may be released by your answer. (11.13–14; 11.17–18) |

| Do you see a man skillful in his work? He will stand before kings; he will not stand before obscure men. (22:29) | As for the scribe who is experienced in his office, he will find himself worthy to be a courtier. (17.16–17) |

| When you sit down to eat with a ruler, observe carefully what is before you, and put a knife to your throat if you are given to appetite. Do not desire his delicacies, for they are deceptive food. (23:1–3) | Do not eat food in the presence of a noble or cram your mouth in front of him. If you are satisfied pretend to chew. It is pleasant in your saliva. Look at the cup in front of you and let it serve your need. (23.13–18) |

| Do not speak in the hearing of a fool, for he will despise the good sense of your words. (23:9) | Do not pour out your heart to everybody, so that you diminish respect for you (yourself). (22.11–12) |

Is There a Literary Dependence between the Writings?

While the similarities are apparent in a side-by-side comparison, there are also numerous differences and other factors that caution against overplaying the potential link.

(1) Difference in length and structure. The Egyptian writing is much longer than this section of Proverbs. Amenemope has thirty chapters that range from seven to twenty-six lines, while the Sayings of the Wise has around four lines per strophe. In addition, in their efforts to find parallels to match the thirty chapters, scholars often make artificial or dubious divisions in the Sayings of the Wise. Moreover, interpreters must view the preamble as the first “saying” in order to arrive at thirty, but the preamble is more likely to be distinguished literarily from what follows. This is also the case in Amenemope, where a three-stanza (48-line) introduction sets the context for the writing prior to the first chapter.

(2) Difference in order. The topics are arranged in a different sequence in the two texts. The Sayings of the Wise follows a progression from poverty/wealth to life/death. Amenemope, however, appears to follow a rather different course, moving from one ethical topic to another, usually centering on the three themes of property rights, civil strife, and conduct at the temple.

(3) Difference in theme. Only around one-third of the chapters of Amenemope (11 out of 30) bear some thematic correspondence to the Sayings of the Wise. In addition, the themes of both writings may be found in other ANE writings, such as the Mesopotamian wisdom writing Counsels of Wisdom or the Egyptian writing The Instruction of Ptahhotep. Forcing correspondence to Amenemope means that the author draws only from that Egyptian writing, where there may have been other ANE writings the author had familiarity with.

(4) Difference in theology. The Sayings of the Wise carry a monotheistic orientation clearly centered upon YHWH. The divine name appears five times (22:19, 23; 23:17; 24:18, 21), along with references to YHWH as redeemer (23:11) and as the one who weighs hearts (24:12). Amenemope carries a polytheistic framework, with references to numerous gods within the Egyptian pantheon, including Horus, Re, Shu, and others. In addition, the polytheistic impulse of Amenemope is based on transactional power dynamics: the official-in-training must behave carefully so as to give no offense to the capriciously powerful gods. The Sayings of the Wise, on the other hand, recognize God’s role as being on the side of the weak and marginalized: He will bring them justice as their advocate (22:23; 23:11) and will show them compassion even when they are enemies (24:18). YHWH is thus to be feared above all because of his sovereign power (23:17; 24:21).

(5) Required emendation. Much of the alleged dependence derives from a questionable understanding of the word thirty in Proverbs 22:20 as correlating with the thirty chapters of Amenemope. The word often emended to “thirty” is understood best as a reference to the “officers” who are being trained in the royal court. The plural form of “the wise” in the heading “Sayings of the Wise” presupposes that under the divine inspiration of the biblical text the author of Proverbs 22:17–24:22—whether Solomon or a later sage—is reshaping material from multiple intellectuals. For this reason, Amenemope, together with other wisdom writings available to the final author(s) of Proverbs, may have been drawn upon and reworked without necessitating a charge of “plagiarism” on outside sources.