Christian Platonism: Friend or Foe?

Christian Platonism. Friend or Foe?

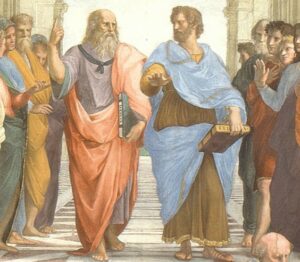

The Christian system has long been dogged by the question of philosophical grounding and the ancient comparison between Aristotle and Plato. Which (if either) of these philosophical models best sustains Christian theology?

Aristotelianism, with its fixation on the observable and the material, is easily scorned. Its shockingly immanent version of Christianity, which dominated the Modernist period, eviscerated transcendence from everything that it touched. It savaged the Bible’s authority with its historical-critical method of interpretation; it domesticated and practically eliminated God with its suppression of the supernatural; and it reduced the function of the church to social/ethical efforts in the pursuit of a utopian now. Aristotle has not been a friend to Christianity.

It is not surprising, then, that Christianity’s long recovery from Modernism has featured the reemergence of the classic alternative—Platonism—as the superior platform for sustaining the Christian system. Barth was its principal early champion, and for those who imagined the choice to be a binary one (Christian Aristotelianism or Christian Platonism), the latter seemed obvious.

Christian Platonism grounds all that can be observed in invisible, timeless “forms” that constitute the basis of all reality. What can be observed by the senses is not “real,” per se, but is metaphorical of true, transcendent realities that cannot be seen. And as is true in all Platonic philosophies, the goal of Christian Platonism is to escape the here-and-now cave of the sensible and to experience the transcendent with the whole soul. But what does this look like? Well, a few examples:

1. In hermeneutics, the Christian Platonist views the historical-grammatical method of interpretation as a mere crutch to raise the reader to a spiritual connection with God. Its “literal” message is not without value but never comprises the whole divine message. Rather, it is the typological (analogical-allegorical), tropological (moral), and anagogical (mystical) senses of Scripture where the Christian finds true knowledge. There are no “rules” by which this knowledge may be discovered (that would be too Modernist); rather, it must be divulged “from above.” See, e.g., Craig Carter’s Interpreting Scripture with the Great Tradition: Recovering the Genius of Premodern Exegesis.

2. In eschatology, the Christian Platonist ridicules any emphasis, say, on ethnic distinctions, land promises, or an earthly throne and temple (much less sacrifices offered in that temple!!); the idea of an eternal stewardship of a new earth as terribly facile. Instead, eternity will chiefly consist in an eternal beatific experience of knowing God as God—not with our paltry senses, but with an ineffably whole-souled intuition evocative of theosis as it has been historically expressed. See, e.g., Hans Boersma, Seeing God: The Beatific Vision in Christian Tradition.

3. Christian Platonism even alters (subtly) certain orthodox conceptions of Theology Proper and Christology in ineffable moments of mystery where God blurs lines of distinction in epistemology and ontology between the Creator/creature, and in the hypostatic union:

- God reveals his secret gnosis (yes, that’s a provocative term, but I stand by it), undiscoverable to the natural reader but accessible to the exceptionally pious.

- The condescension/kenosis of God is so complete that God effectively becomes us; the death of God as God becomes the center of the biblical story (Moltmann).

- Versions of the beatific vision mute the incomprehensibility of God as the creature enjoys moments of holistic intuition of God.

And so forth. I am becoming concerned that we are witnessing, in the recent ascendency of the “premodern” in contemporary evangelical literature, the triumph of Barth and ultimately of Gnosticism in the evangelical church—and not just along its crumbling perimeter, but at its very center.

Dr. Snoeberger, interesting article. I’m just finishing North’s book “The Gospel and the Greeks” which has some overlap here.

Can you elaborate on your final bullet point? I have not heard of this sense of beatific visions and am trying to understand. Thanks!

In Boersma’s book, he surveys a wide range of historical options on the beatific vision. Several anticipate the beatific vision in terms of transcendent knowledge of God (not Christ) with the whole soul (not the senses) in a moment of absorption (i.e., theosis) that seems to blur the line of demarcation between Creator and creation and suggest a “full” knowledge of God. I get uncomfortable with some of these Platonic extremes.

Very helpful summary and a very helpful article. Thank you.

Well said! I share your concerns.

This is really interesting. Thanks for writing. I haven’t heard this thought experiment before. There is a lot we still don’t understand about the universe God created. It seems we see through a glass darkly in more ways than we like to admit. I can’t help but wonder if there are likely elements of truth in the platonic view, mixed in with the extremes. I wonder if some of the platonic views are the first sketches of what is now called quantum mechanics. If I remember correctly, Plato theorized atoms existed, but called them something different. Or maybe it’s the evolution of our understanding of our reality, an attempted reconciliation of what our senses can perceive and that which our sense cannot perceive but are nonetheless there in front of us. So many questions for which we will likely not have answers anytime soon. I believe one thing is certain, our world is stranger than Christian’s like to think and we will endlessly be awed by God’s creation, that which we can see now and that which we will see later.