Kruger’s “Bully Pulpit”: A Review

It is not often that I endorse a book I did not enjoy reading. Nevertheless, I heartily endorse Bully Pulpit, a book about the abusive tactics of some church leaders and the spiritual devastation left in their wake.

Michael Kruger, a theologian best known for his work on the biblical canon, here ventures into the practical theology field. His writing is not the source of my displeasure; indeed, he writes with characteristic organization and purpose. My displeasure comes from the dissonance that exists between my image of a godly pastor and the image cast of abusive shepherds. This book evidenced that the false shepherds of Israel still exist in the church today (Ezekiel 34).

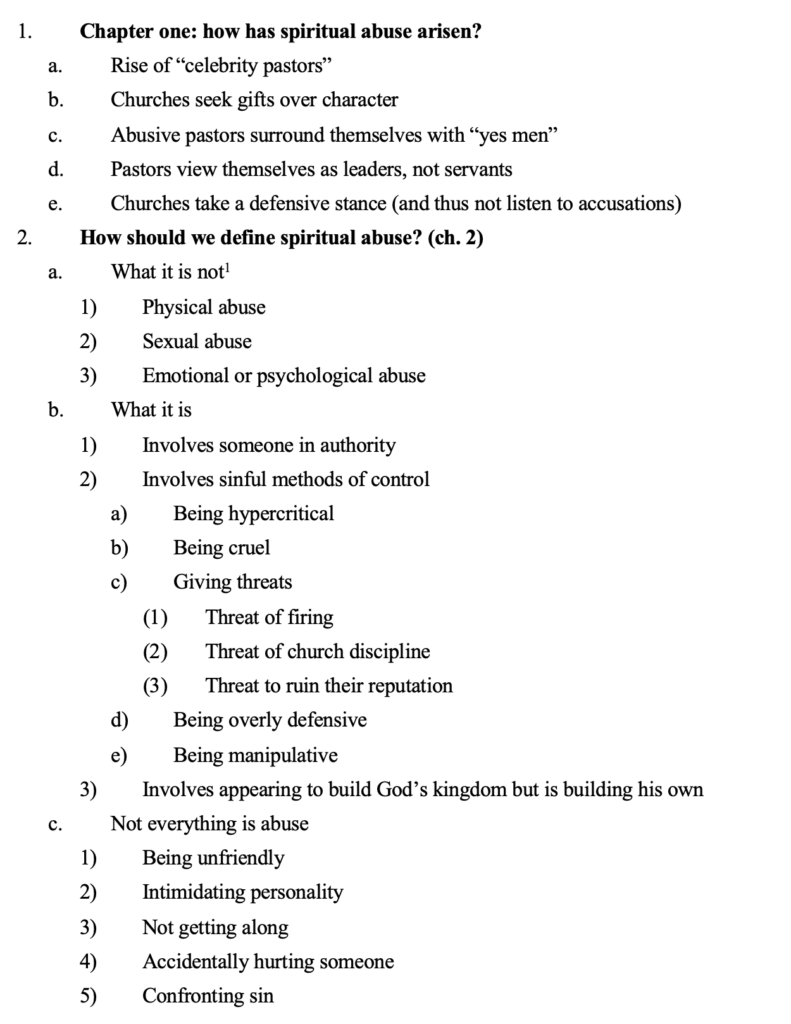

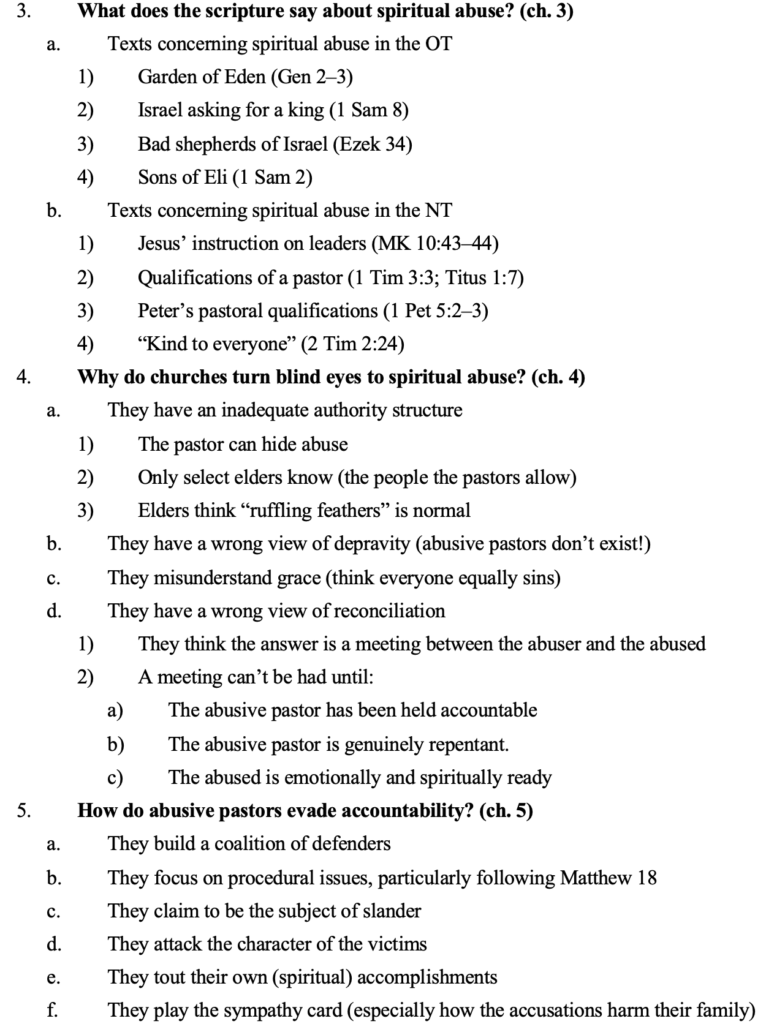

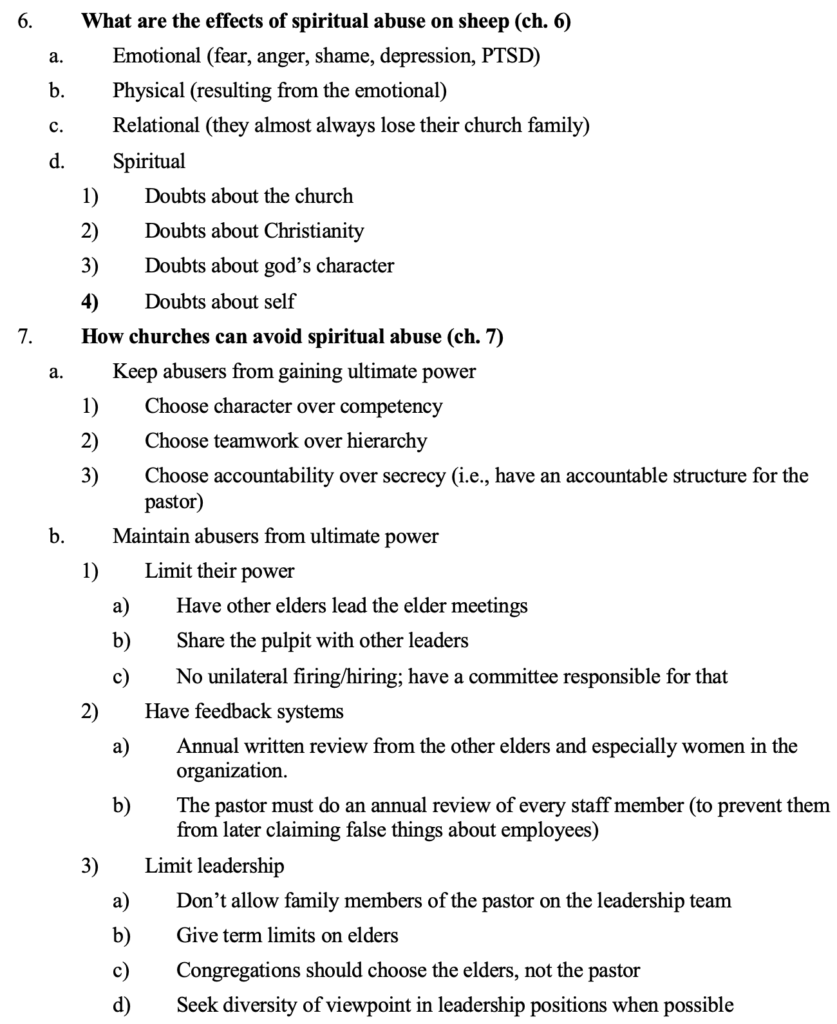

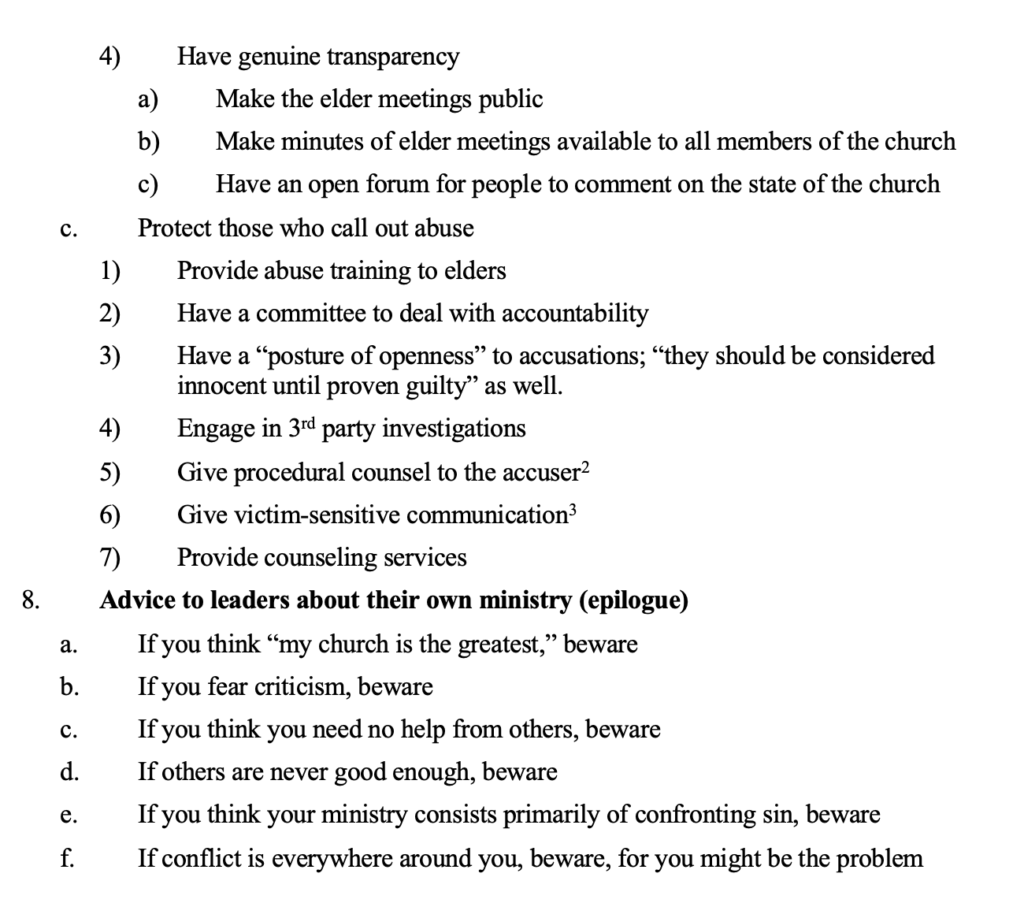

The following is my own broad analytical outline of the book:

My largest takeaways were the following:

- I believe it is true that Churches may be opening the door for abusive pastors because “We would rather have a leader who will beat up our enemies than one who will tenderly care for the sheep” (XV)

- The Power Dynamics are strongly in favor of the potentially abusive Pastor.[4] Accordingly, deep concern should exist to make sure abused sheep have the opportunity to be heard.

- Many abusive pastors think they are doing the work of God. “He may be convinced he’s building God’s Kingdom, not his own. In his mind, he’s so significant to the work of the Kingdom, so important, so valuable, that he feels justified in doing nearly anything to keep that ministry on track. If people get run over, then that’s because they got in the way of Great Kingdom work he’s doing—collateral damage, so to speak. In a sick, twisted way, he’s crushing people for the glory of God. . . . The success of their ministries, at least in their own narcissistic minds, is proof enough of their innocence” (34–35).

- What is viewed as “Ministry Success” sometimes has little to do with genuine ministry success: “ministry accomplishments and character references are not determining factors in whether a pastor is abusive. Virtually any Christian leader who’s been in ministry for a decent length of time could trumpet his accomplishments and find people who’ve been blessed by his ministry. Indeed, how many local pastors could go toe to toe with the accomplishments of someone like Ravi Zacharias? or Bill Hybels? or Mark Driscoll? And yet they were all perpetrators of abuse” (94).

- If I am ever asked to be on a pastoral church committee, I would like to follow Kruger’s advice on 114–115; namely, reach out to the previous elders as well as the previous staff members (especially female staff) to get references.

[1] Note that Kruger would say that other forms of abuse may be a part of spiritual abuse, but he notes that these are different categories distinct from the type of abuse he desires to discuss in this text.

[2] Based on the idea that the potential abuser has more knowledge of the proceedings of such an abuse investigation, the potential abused needs to have direct counsel.

[3] Based on the idea that the pastor will be kept aware, the accuser needs to also be kept aware of the status of the situation.

[4] Kruger rightly notes that this is what goes through many people’s minds when an accusation first appears: “Is it more likely that this respected pastor has been mistreating, bullying, and domineering his flock? Or that people are oversensitive and get their feathers ruffled by a strong leader?” (67).

Though I generally appreciate Kruger’s work and that someone is thoughtfully addressing this subject, I immediately disliked the terminology “spiritual abuse.” We cannot deny the fact of spiritual leaders who have not demonstrated shepherd-like character, some leverage their leadership to abuse in other ways. But, does a spiritual leader who abuses or exhibits poor character warrant a special label? What do you think?

Good question. One of the interesting things about language is that words appear when needed. This is why Americans have one word for rice, while many Asian countries have numerous words for it. In relation to Westerners, who eat rice infrequently, it is not important enough to warrant diverse terminology. The more recent addition of the word “spiritual abuse” may be an attempt to highlight its frequency (and thus a need for a special designation). In the end, I think those who have seen or experienced it might say that the word is needed, while those who have not seen it with any frequency might say it is unnecessary.