by Timothy Hughes1

It happens to every elementary Greek student. Just when he is getting used to verbs in his vocabulary lists ending in –ω, a whole new pattern of verbs emerges in his vocabulary assignments. Suddenly he is confronted with ἔρχομαι, βούλομαι, δέχομαι, and other vocabulary forms that mysteriously appear with middle/passive endings. And yet the English glosses provided seem active enough—they appear neither passive nor reflexive. He dutifully memorizes the vocabulary for the day and comes to class, hoping for an explanation. The traditional answer to the befuddled student has often come in the form of a lesson on a deponency.

When I first started teaching elementary NT Greek, the deponent verb was familiar territory for me and an easy concept to teach. I had been happily parsing these verbs for years. As I would explain, deponent verbs are middle or passive in form, but active in meaning. Typically, verbs so classified have no attested active form—certainly not in the NT. And for some reason not entirely known to us, I would continue, the middle/passive form essentially serves as the active form. Looking back on this explanation, I regret that I missed an opportunity to ensure my students better understood and appreciated the middle voice.

As scholars have continued to study the semantics of the Koine voice system, an increasing number of NT Greek teachers have come to conclude that “deponency” (at least as often taught or caught in NT Greek classrooms) is a suspect category. This paper summarizes some of these findings and argues that Greek teachers today should eliminate deponency as a category in their pedagogy, and replace it with a more robust understanding of the Greek middle voice. Pastor-scholars, as well, should consider reassessing their understanding of the category of middle-only verbs, since these verbs occur frequently in the New Testament.

This conversation is more important than it may initially seem, because perpetuating a lack of clarity on what is actually occurring with so-called “deponents” aggravates and reinforces these four all-too-common misperceptions among students and even expositors: (1) that active and passive are the main voice choices in Greek and the middle is a sideshow; (2) that if it sounds active in English, the meaning must be active in Greek; (3) that the “true” middle can/should always be translated as a reflexive or with a “for itself” clause; and (4) that since active/passive voices are the main voices, and most middle forms are deponents, it is probably not essential to learn much about the middle other than its forms (in order to parse all those deponents).

Unfortunately, we set our ourselves up for these bad assumptions if we explain middle-only verbs (to our students or to ourselves) in the way I have already admitted I used to explain them. Too many students of NT Greek pay little meaningful attention to the middle voice in general—and it is likely that this malady stems in large part from the way teachers pass along the concept of “deponency” to students while presenting a narrow description of the middle voice’s semantic range.2 In the meantime, we are missing an opportunity to teach and model linguistic and historical sensitivity. We are missing an opportunity to better immerse ourselves, without filter, into the first-century world. We might even be missing exegetical precision in interpreting passages involving middle-only verbs. And too many, I fear, are almost entirely missing something that all of us ought to consider very important: one of the three voices in the language we have been tasked to teach them.

Middle Voice Defined

Simply put, voice shows how the action or state indicated by a verb relates to the grammatical subject of that verb.3 What relationships are possible? Traditionally, three voices (in terms of form and function) have been identified in Koine. The curriculum from which I taught displayed these different voices in a chart indicating the nature of the relationship indicated between the action and the subject:4

Definitions from other Greek grammars help us fill out a picture of the Koine middle voice. Porter states that “the Greek middle voice expresses more direct participation, specific involvement, or even some form of benefit of the subject doing the action.”5 Neva Miller’s more involved explanation is helpful: “The middle voice shows that not only does the subject perform the action in the verb, but that the effect of the action comes back on him. He does the action with reference to himself. He is involved in the action in such a way that it reflects back on him. The action calls attention to him in some way. For example, I washed myself.”6 Wallace elaborates on the middle voice: “in the middle voice the subject performs or experiences the action expressed by the verb in such a way that emphasizes the subject’s participation.”7 According to Barber, “When a Greek author chooses the middle over the active voice for a particular verb, he is expressing what is usually described by Greek teachers as the ‘involvement’ of the subject in the action—the fact that the agentive subject is also affected in some way by the action.”8 Barber’s definition is helpful because it avoids giving the impression that the Greek middle is primarily a narrow reflexive or indicative merely of positive self-interest. Moving to a broader, more typological and cross-linguistic understanding of the middle voice, Lyons states: “The implications of the middle (when it is in opposition with the active) are that the ‘action’ or ‘state’ affects the subject of the verb or his interests.”9

What is it, then, that the middle voice form encodes at the baseline level? In line with these definitions and with the actual usage of the middle voice in Koine, I view the middle voice form as grammatically encoding subject-affectedness.10 The middle forms are appropriate for expressing a verbal situation in which the subject itself is in some way affected by the action of the verb. Of course, there are a number of different sub-categories of subject-affectedness and thus a number of different event-types for which the middle voice forms are appropriate, but the over-arching semantic idea in the middle voice can be viewed as an expression of subject-affectedness.11

Dealing with Deponency

When I first started teaching Greek and it came time to teach my elementary students about verbs that only occur in the middle or passive voice, I would explain that these verbs are middle or passive in form, but active in meaning. I viewed deponent verbs as an exception to the rule, as a sort of violation of an otherwise orderly voice system in NT Greek—and presented them as such. In doing this, I was not alone, and I had Greek grammars to back me up.

Mounce, one of the most popular elementary texts, presents the deponent verb in a similar way:

This is a verb that is middle or passive in form but active in meaning. Its form is always middle or passive, but its meaning is always active…. You can tell if a verb is deponent by its lexical form. Deponent verbs are always listed in the vocabulary sections with passive endings…. If the lexical form ends in –ομαι, the verb is deponent.12

Dana and Mantey, an older but helpful grammar, states that “deponent verbs are those with middle or passive form, but active meaning.”13 Wallace’s volume fell in line with traditional grammars in its definition: “A deponent middle is a middle voice verb that has no active form but is active in meaning.”

Perhaps, though, it was Wallace’s work itself that during my years of teaching Greek as a PhD student first began to open my eyes to the fact that there is more complexity to the issue than I had first realized. Although I taught my students that if the lexicon entry for a verb had middle endings, they could assume the word was deponent, Wallace indicates that the “ideal approach” goes a step or two further:

When an exegetical decision depends in part on the voice of the verb, a more rigorous approach is required. In such cases, you should investigate the form of the word in Koine (conveniently, via Moulton-Milligan) and classical Greek (Liddell-Scott-Jones) before you declare a verb deponent. Even then, you should not be able to see a middle force to the verb.14

Wallace’s presentation showed me that some of the verbs I would have classified as “deponent” may, in fact, be middle in meaning as well as in form. In fact, Wallace goes on to supply a list of “some verbs that look deponent but most likely are not.”15 The list includes some vocabulary forms that I had been giving to my students as “deponents” under the definition “middle or passive in form, active in meaning.”

Yes, there actually are middle-only verbs that can be classified as true middles. After all, it would be arbitrary to assume that just because a verb shows up only in the middle voice, ergo we should ignore middle voice morphology and assume the middle voice is standing in for the active. Just because a Greek middle-only verb sounds active to English ears—in English translation—does not mean that in Koine this middle verb carried the meaning of the active voice. Many Greek middles—including those that have active forms—can be translated in English in a way that doesn’t seem or sound active to English ears. The temptation as English speakers can be to assume the meaning is active, simply because we don’t have a middle voice with which to compare it or translate the middle voice Koine verb. Upon closer scrutiny, it is apparent that for many of these supposedly deponent verbs, the action does in some way affect the subject, and, thus, it makes sense that the verb should occur in the middle voice.

What was a new discovery for me was really nothing new. Had I been reading more widely all along, I could have spared myself (and my students) my earliest notions of deponency. I mentioned Wallace helped me realize that many of the middle-only verbs I had been analyzing as active in meaning were true middles. But even older works could have tipped me off to this. William Hersey Davis’s Beginner’s Grammar of the Greek New Testament, in dealing with these verbs notes that “these verbs have been called ‘deponents’ (middle or passive) because it was difficult to see the distinctive force of the verb. Yet it is not hard to recognize the personal interest of the subject in the verbs in the middle voice.”16 If in 2009, when I first started teaching, I had picked up the 2009 translation of Wackernagel’s Lectures on Syntax (originally given in German in the 1920s), I could have furthered my understanding by reading his helpful discussion of what he refers to as the “so-called deponents,” especially his summary of the issue: “In other words, deponents are simply middle verbs which have no active forms and our task becomes to discover the middle meaning in the deponents.”17

As a busy graduate student and a relatively inexperienced elementary Greek instructor, I had seen enough to begin making small adjustments. What I was not fully aware of at the time was that, as I was beginning to work through these issues in my own thinking, some of the brightest minds in the contemporary study of NT Greek were already reaching a consensus that it was time to set the category of deponency aside altogether.

A Growing Consensus in Scholarship18

Tucked away in the back of Friberg’s analytical lexicon (2000) is a little treasure—Neva Miller’s appendix titled “A Theory of Deponent Verbs.” Miller’s essay demonstrates how it is possible to take verbs conventionally analyzed as deponents and place them in categories that make sense of them as true middles in light of middle voice semantics.19 In the traditional analysis of middle-only verbs, Miller argues, “The student can only conclude that…[these middle verbs] appear to communicate in a rather clumsy way concepts that appear clear enough in other languages as active verbs.”20 Miller suggests “an alternate approach to deponency,” one in which we “examine each such verb for its own sake and allow it to speak for itself.” “Since the middle voice signals that the agent is in some way staying involved in the action,” Miller argues, “It is appropriate to ask, How is the agent involved?”21 Miller proceeds to offer a representative display of NT Greek “deponents” broken down into seven major categories: reciprocity (positive interaction, negative interaction, positive and negative communication); reflexivity (including self-locomotion); self-involvement (intellectual activities, emotional states, volitional activities; self-interest; receptivity (where the subject is “the receiver of sensory perception”); passivity (where “involuntary experiences” are in view); and state or condition (where “the subject is the center of gravity”). Miller’s article presents an intriguing argument: that through a more robust understanding of and appreciation of the range of meaning indicated by middle morphology, it is possible to achieve a better understanding of what the voice form of these verbs is actually there to communicate. And, as Miller concludes, “it would be worthwhile for exegetes, students, and translators to look for the enriched meaning being communicated by this category of verbs by letting each middle or passive ‘deponent’ verb speak with its own voice.”22

Even as Miller wrote, scholars were looking for this “enriched meaning.” Bernard Taylor’s 2001 SBL paper “Deponency and Greek Lexicography” finds deponency to be a concept imported from Latin grammar and foisted on the Koine middle voice and concludes that “for Greek, then, what needs to be laid aside is the notion of deponency.”23

Carl Conrad, in an unpublished paper, argues that “technology and assumptions either implicit in the teaching or openly taught to students learning Greek seem to me to make understanding voice in the ancient Greek verb more difficult than it need be.”24 He continues:

In particular I believe that the meanings conveyed by the morphoparadigms for voice depend to a great extent upon understanding the distinctive force of the middle voice, that the passive sense is not inherent in the verb form but determined by usage in context, and the conception of deponency is fundamentally wrong-headed and detrimental to understanding the phenomenon of ‘voice’ in ancient Greek.25

Conrad believes that “the fundamental polarity in the Greek voice system is not active-passive but active-middle” and argues that “the middle voice needs to be understood in its own status and function as indicating that the subject of a verb is the focus of the verb’s action or state.”26 Furthermore, in dealing with verbs typically analyzed as aorist passive forms with a deponent function, Conrad argues that “we need to grasp that the -θη- forms originated as intransitive aorists coordinated with ‘first’ -σα aorists, that they increasingly assumed a function identical with that of the aorist middle-passives in -μην/σο/το κτλ. and gradually supplanted the older forms.”27 Conrad essentially argues that the middle voice covered the passive function and -θη- marker is to be seen as an alternate middle form that originated as an intransitive form (in certain tense-forms) within the middle voice. In fact, Conrad goes on to suggest that we consider “middle” and “passive” forms together as a single morphoparadigm.28 Conrad’s contribution certainly furthers the conversation and puts on the table several well-argued ideas that deserve consideration.29 On a website that provides Conrad’s latest updates to his perspectives on this issue, he notes:

Most of what is set forth here is already clearly indicated in such standard reference works as A.T. Robertson’s big NT Grammar and in Smyth’s Greek Grammar…. What is aimed at here is the simplification and clarification of what was already, to a considerable extent, understood by at least some traditional grammarians.30

Rutger Allen, in his dissertation on the middle voice in Ancient Greek, demonstrates that media-tantum (middle-only verbs or “deponents”) should be treated as semantic middles.31 Critiquing conventional treatment that deals with media-tantum separately from oppositional middles, Allen notes that in conventional treatment while the latter “are distinguished purely on the basis of semantic criteria,” the former are “distinguished by a completely different criterion, namely the non-existence of an active form.”32 Given the fact that middle-only verbs can be explained in terms of middle semantics, it makes little sense to separate them out as if the absence of an active form somehow implies that these middle-only verbs cannot express middle meaning. Allen provides a helpful listing of categories in the realm of middle semantics within which middle-only verbs tend to fall: beneficiary/recipient; body motion; emotion/cognition; volitional/mental activities; reciprocal; perception; and speech act.33

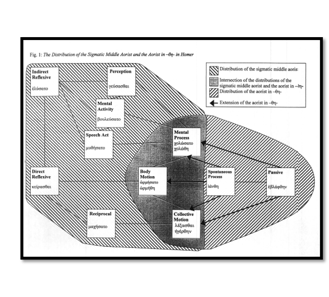

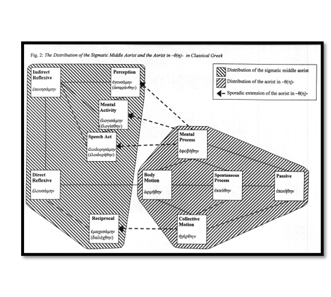

Allen’s third chapter discusses aorist middle and passive forms. This is highly relevant to the current discussion, since one of the main challenges to eliminating the concept of deponency (and instead appealing to a more robust appreciation of middle semantics) is the issue of deponents that in the aorist tense-form appear with prototypical “passive” endings. Allen notes that “in the course of the history of the Greek language, a gradual expansion of the passive aorist form can be observed. This expansion takes place mainly at the cost of the sigmatic middle aorist.”34 Allen finds that the passive aorist form extended itself by “connected paths through the semantic network.”35 Allen’s charts, supported by his more detailed analysis and discussion, illustrate the encroachment of the passive forms upon middle semantic territory in Homeric and Classical Greek and are reproduced below.36

Allen’s work, while not focused on Koine Greek, is a significant contribution that seriously grapples with the meaning of the Greek middle voice—a resource that will continue to be referenced in ongoing conversation regarding the Greek middle. It supports the contention that deponency is not a helpful category, offers help in understanding and classifying middle verbs (including middle-only verbs), and provides information that is helpful in dealing with the challenge of what to do with passive forms (in the aorist) of verbs lacking active forms—verbs that have traditionally been analyzed as deponents but that I suggest we ought to view as true semantic middles.

Jonathan Pennington first wrote on the topic of deponency in 2003.37 In 2009, he argued:

The grammatical category of deponency, despite its widespread use in Greek grammars, is erroneous. It has been misapplied to Greek because of the influence of Latin grammar as well as our general unfamiliarity with the meaning of the Greek middle voice. As a result we have failed to grasp the significance of the Greek middle. Indeed, most if not all verbs that are traditionally considered ‘deponent’ are truly middle in meaning. But because the Greek middle voice has no direct analogy in English (or Latin), this point has been missed…. Additionally, a rediscovery of the genius of the Greek middle voice has ramifications for New Testament exegesis.38

Pennington goes on to lament the fact that “the category of deponency is still used universally in our presentation of Greek grammar,”39 then, after challenging the idea of deponency, offers a positive explanation of what is going on with middle-only verbs, appealing to Miller’s categories as well as to the work of Suzanne Kemmer.40 He also includes a helpful section discussing the potential objections raised by verbs that are middle only in the future tense-form and by aorist passive deponents. He offers a perspective on the impact on the study of the New Testament, observing that “sensitivity to the nuances of the middle voice opens new possibilities when encountering middle forms in the New Testament texts” and that “both middle-only verbs and those which fluctuate between the two voices can be more fully appreciated in light of a fuller understanding of the Greek middle.”41

Based on skeletal handouts accompanying his 2010 and 2012 SBL presentations, and confirmed by personal conversation with Pennington in 2019, Pennington has adopted Carl Conrad’s schema for viewing “aorist middle” forms and “aorist passive” forms as two versions of a “middle-passive” or “subject-focused” morphoparadigm.42 Pennington was not the only presenter, obviously, at the 2010 and 2012 SBL sessions on this topic. In 2010, Constantine Campbell presented and along with the other presenters “argued that the category of deponency ought to be abandoned.”43 At the same session, Bernard Taylor demonstrated that deponency was a concept imported from Latin. In a revision of this paper that was published in 2015, he concludes that “it is well past time to return deponency to Latin, and attune the ear to the nuances of the Greek middle voice.”44 Porter presented on “Criteria for Determining the Concepts of Voice and Deponency in Ancient Greek.”45

An SBL session in 2012 was actually titled “We Killed Deponency: Where Next?” So strong is the developing consensus that Campbell states, “While not all Greek professors are yet convinced that deponency should be abandoned, there is a consensus among most scholars working in the field that it should.”46

Some Challenges

Some of the greatest challenges to this viewpoint are the “aorist passive deponents” and “future deponents.”47 I have already addressed the aorist passive issue above, particularly in the section where I overviewed Carl Conrad’s contribution and Rutger Allen’s dissertation. It appears that the passive forms are, during the Koine period, well into their encroachment of middle semantic territory. The close relationship between the middle and the passive, the fact that the passive voice was developed after the middle voice was already clearly established, and the evident expansion of the usage of the -(θ)η- forms all favor the conclusion that the issue of so called “passive deponents” is not a good reason to continue pedagogical reliance on the category of deponency. There is no reason to get the active voice involved or to appeal to an explanation like “middle or passive in form, active in meaning.” Even if one parts ways with Conrad and Pennington and views the forms as separate passive forms (rather than an alternative or secondary form within a single middle/passive morphoparadigm expressing subject-focus), any mismatch between form and function would be in the context of an intramural contest between the middle and passive forms. No recourse to the concept of deponency is needed; it is not helpful to identify what is going on as a passive form taking on active semantics. If anything, it would appear to be the case of a passive form taking on middle semantics.48

The issue of future deponents, or verbs that use an active form in the present but are middle-only in the future, presents another challenge. In this regard it is helpful to realize that there may be a closer relationship between voice and other semantic and pragmatic features of the Greek verb such as aspect, tense, and Aktionsart than is sometimes realized. Egbert J. Bakker, discussing objective intransitive one-participant events notes that for these events, in the future “the morphology is consistently middle” and offers an explanation:

The affinity between future and middle, here and in other cases, has puzzled philologists, but is in fact easy to explain…. On account of its connection with volitionality, future tense presents an event as a mental disposition, an intention, and this naturally explains the affinity between “middle” and “future”, since volitionality as the sole transitivity feature of an event (i.e. when agency and causation are absent) involves affectedness.49

Pennington’s discussion of this issue is also helpful. He points out that “because the future tense can only present an event as a mental disposition or intention, the middle voice serves well in many instances to communicate that sense.”50 Citing Klaiman’s cross-linguistic study, Pennington says that “there is a close semantic connection in many languages between the middle voice and the future tense.”51 Further work may be needed to understand future middles in a deponent-less model of the Greek verb, but the difficulties here do not appear to be insurmountable nor do they negate the contention that, in general, many true middles have been swept into the black hole of the deponency concept rather unfairly.

Finally, it seems probable to me that some middle-only verbs are showing conventionalized forms. Conventionalization, in my mind, is likely a factor with some of these middle-only verbs. But admitting that some middle forms may have become conventionalized is not the same as saying that there is a whole category of verbs in which middle forms code for active semantics. Particularly in light of evidence that the middle voice was still understood in the Koine period, there is no need to assume that conventionalization negates the basically middle force of all or even most middle-only verbs.52 It is simply not necessary essentially to dismiss out of hand the vast majority of middle-only verbs as encoding active meaning.

For pedagogues nervous about a potential over-reaction against deponency and convinced there is still some merit to the concept, perhaps the following approach would provide an acceptable via media: consider teaching the verbs as middle-only verbs, pointing out the wide semantic range of the middle voice; but feeling free to suggest to students that a number of these middle-only verbs may well have become conventionalized and have lost their distinctive middle edge in the consciousness of the typical Greek speaker or writer. Some may wish to retain Wallace’s brief list of true deponents, while reclaiming the many others. And, depending on the level of your students, you may choose to discuss some of the complexities and challenges that make it difficult to provide a unified explanation for the all of the phenomena (as demonstrated in this article).

But in any case, surely it is best to avoid casually teaching a sweeping deponency that oversimplifies the issues and teaches students to look at Greek through the lenses of English grammar at the expense of understanding and appreciating the middle voice and many of its occurrences in the NT. In our pedagogy of the Greek verb, we need to adopt an approach that intentionally and adequately prepares students for the forms they will encounter, without unnecessarily reinforcing the inclination they will already have, as English speakers, to simply pass over the middle voice as an oddity that is not important since it does not conform to their preunderstanding regarding verbal voice.

Does This Really Make A Difference?

Continuing to teach and think of middle-only verbs as “middle in form, active in meaning” will only serve to aggravate and reinforce these four all-too-common misperceptions among Greek students (and, perhaps, busy expositors). 1) Active and passive are the main voice choices in Greek and the middle is a sideshow. 2) If it sounds active in English, the meaning must be active in Greek. 3) The “true” middle can/should always be translated as a reflexive or with a “for itself” clause. 4) Since active/passive voices are the main voices, and most middles are deponents, it’s probably not essential to learn much about middles other than the forms (in order to parse all those deponents).

In contrast, what could be gained by discarding (or minimizing and adjusting) the category of deponency and, instead, adopting an approach that analyzes middle-only verbs as middles in their own right?

First, it may result in a recovered appreciation and awareness of middles in general. Those who make this adjustment in their thinking (and pedagogy, where applicable) may start giving middles more of the attention they deserve. This is a general benefit, but one worth mentioning. The mere availability to dismiss so many middle forms as “deponents” may lull some readers of the Greek NT into the bad habit of ignoring middles in general—or even committing the offense of trying to settle a theological argument by calling something deponent when it is not so.53 A student who accidentally misapplies the category of deponency to oppositional middles is missing out on opportunities to understand and appreciate what may be a meaningful distinction. On the other hand a student who has been taught to appreciate that fact that many (at least) middle-only verbs can be seen as true middles, and who has been taught the full range of middle semantics, is more likely to engage in fruitful reflection on oppositional middles, as well.54

Second, some middles that have been dismissed as deponent and treated as “active in meaning” may prove to be material for fruitful exegetical reflection—even though the English translation will seldom be impacted. While the payoff in this area may not seem immediately and demonstrably significant in a plethora of showcase passages, better understanding of the semantics of middle-only verbs, if used responsibly, will likely only help, not hurt, exegesis of specific passages.

Third, this approach would result in a broadened range of available categories for understanding all middles in the Greek NT (both middle-only verbs and oppositional middles). The options are far more than what many elementary Greek textbooks might imply, and the whole process of coming to a more robust understanding of middles—both broad enough and nuanced enough to encompass all or most occurrences—has implications for exegesis of all middles (not just middle-only verbs). It makes little sense to require students to analyze genitives, nominatives, accusatives, participles, infinitives, and even tenses to identify their “uses” and yet to leave the full semantic richness of the middle voice untouched and unmentioned. Any teacher who sees these usage exercises as helpful ought also to see the potential in careful thinking about the verbal situations represented by middle-only verbs. The categorical work of Neva Miller, Rutgar Allen, and others could easily be condensed into lists, with English and Greek examples, that would help students quickly grasp the general semantic territory covered by the middle voice.55 Setting aside—or significantly adjusting—the way “deponency” is often taught forces us to expand our understanding of middle semantics and opens up avenues for deeper thinking about the nature of the verbal events represented by middle verbs.

Fourth, the accompanying exercise of wrestling through some of the related issues, such as the so-called “passive deponents” for example, may provide further exegetical benefit. For instance, understanding the overlap of semantic territory covered by the “aorist passive” and “aorist middle” forms may result in increased understanding of some of the “passive” forms in the NT that aren’t actually passive. By understanding that the -θη forms encroached upon an increasingly wide swath of middle semantic territory during the Koine period, we open up a whole set of middle categories with which to analyze the nature of the verbal event in question when dealing with aorists in -θη.56 Acts 2:6 provides an example: “And at this sound the multitude came together, and they were bewildered [συνεχύθη], because each one was hearing them speak in his own language.” Upon looking the form up in a lexicon, the traditionally trained student will see that this verb, listed under the active form συγχέω, is not a “deponent,” so he might immediately assume he has exegetical options here. With any imagination, he could easily start going down an interesting (and perhaps bewildering) exegetical path with this “passive” form—perhaps wasting time or even misleading himself and his hearers. If on the other hand he were equipped with a more full-orbed understanding of middle semantics and aorist morphology, he might be more quick to analyze the form as an aorist middle/passive form (since the -θη forms in aorist often code for middle semantics), with the nature of the verbal event being mental process—one of the categories available to those who have adopted a more robust/full-orbed understanding of middle semantics.57 He will be able to better understand and contextualize what he sees in his lexicon when it tells him that the passive form of συγχέω can mean “bewildered.”

Therefore, in light of the benefits a more nuanced approach may bring, let us at least consider explaining middle-only verbs without appeal to the category of “deponency.” If we deem it wise to retain the category at all (perhaps for a much smaller set of middle-only verbs as Wallace has done), let us explain ourselves carefully while avoiding sweeping generalizations and misleading definitions. We must teach the forms of course. But perhaps we should take a pedagogical cue from Rod Decker’s grammar:

There are some verbs that always occur in the middle form; they use only the C personal ending, never the A set. These verbs do not have an active form. That is, you will never see them with active personal endings (set A). For this reason they are called middle-only verbs. This is a set of verbs that typically has an inherent middle meaning in the very lexis of the word itself. That is, the meaning of the word makes the subject focus of the middle form very natural.58

Decker’s explanation is one example of how we can approach this category of verbs without giving the impression that these verbs do not make sense as middles. If more of us will consider adopting a similar approach, we may be able to take a significant step forward in recovering the middle voice for our students—and maybe even for ourselves.

- Dr. Hughes is Senior Manager of the Office of Ministerial Advancement at Bob Jones University and an adjunct professor of New Testament at BJU Seminary.[↩]

- See Jonathan Pennington, “Setting Aside Deponency,” in The Linguist as Pedagogue: Trends in the Teaching and Linguistic Analysis of the Greek New Testament, ed. Stanley E. Porter and Matthew Brook O’Donnell (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix, 2009), 197.[↩]

- “Voice…indicates how the subject is related to the action or state expressed by the verb” (Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996], 408). “Voice is a form-based semantic category used to describe the role that the grammatical subject of a clause plays in relation to an action” (Stanley Porter, Idioms of the Greek New Testament, 2nd ed. [BLG, 2; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2nd ed., 1994], 62). “The voice of a verb is construed to show how the participants in the action expressed in a verb related to that action” (Neva F. Miller, “A Theory of Deponent Verbs,” Appendix 2 in Analytical Lexicon of the Greek New Testament, ed. Barbara Friberg, Timothy Friberg, and Neva F. Miller [Grand Rapids: Baker, 2000], 423). “Voice indicates the relationship of the action of a verb to its subject” (A Handbook for New Testament Greek, 4th ed. [Greenville, SC: Bob Jones University Press, 2007], 8).[↩]

- Handbook for New Testament Greek, 8. Notice that middle voice was defined third (after the more familiar active and passive voices) and was defined in terms of self-interest or reflexive action.[↩]

- Porter, Idioms of the Greek New Testament, 67.[↩]

- Miller, “Theory of Deponent Verbs,” 424.[↩]

- Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics, 414.[↩]

- E. J. W. Barber, “Voice—Beyond the Passive,” in Proceedings of the First Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (1975): 16, available at https://escholarship.org/ uc/item/6339k77b).[↩]

- John Lyons, Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), 373.[↩]

- See Rutgar Allen, “The Middle Voice in Ancient Greek: A Study in Polysemy” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Amsterdam, 2002), 185.[↩]

- It is helpful to keep Allen’s explanation in view: “In accordance with the usage-based model of grammar, it is conceivable that this abstract schema is less entrenched, and only of secondary importance in actual language use. In speaking and hearing, the language user is more likely to activate the more concrete middle usage types, than the rather abstract superschema of subject-affectedness. For example, it is plausible that, when a Greek heard the word ἵσταμαι in a context without a direct object or external agent, the low-level ‘node’ of the pseudo-reflexive, that specified that the subject undergoes a self-initiated change of state, was activated first and foremost. The abstract schema, with the single implication that the subject is affected, may have been activated less strongly, or not at all.”[↩]

- William Mounce, Basics of Biblical Greek, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003) 150. I am encouraged to see that Mounce’s 4th edition text and its treatment of middle-only verbs is more user-friendly for pedagogues who adopt the recommendations of this article.[↩]

- H. E. Dana and Julius R. Mantey, A Manual Grammar of the Greek New Testament (New York: McMillan, 1927), 163. Dana and Mantey distinguish between the terms defective and deponent. The former has reference to a verb that does not show up in all three voices. Often the concepts are combined and presented under the idea of deponency, as Mounce has done in the section quoted above.[↩]

- Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics, 429–30, emphasis added.[↩]

- Ibid. This list is worth perusing.[↩]

- (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1923), 70–71.[↩]

- Jacob Wackernagel, Lectures on Syntax: With Special Reference to Greek, Latin, and Germanic, ed. and trans. David Langslow (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 160.[↩]

- In this section overviewing key voices in the recent conversation on this issue I am indebted to Constantine Campbell, Advances in the Study of Greek: New Insights for Reading the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015). Campbell’s arguments and summary of recent scholarship in Chapter 4, “Deponency and the Middle Voice” (91–104) provided key sources that have been extremely helpful.[↩]

- Miller suggests that “largely through failure to understand what is being communicated, verbs that show no active voice forms have been relegated to a category called deponent” (Miller, “Theory of Deponent Verbs,” 424).[↩]

- Ibid., 425.[↩]

- Ibid., 426.[↩]

- Ibid., 430.[↩]

- In Biblical Greek Language and Lexicography: Essays in Honor of Frederick W. Danker, ed. Bernard A. Taylor, John A. L. Lee, Peter R. Burton, et al. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 175.[↩]

- “New Observations on Voice in the Ancient Greek Verb” (2002), 1, available at https://pages.wustl.edu/files/pages/imce/cwconrad/newobsancgrkvc.pdf.[↩]

- Ibid., 2.[↩]

- Ibid., 3.[↩]

- Ibid., 5. Bolstering his argument is the historical reality that Proto-Indo-European and early Greek voice systems had only two voice paradigms, and there were no distinctly passive forms (ibid., 6). This is not a blind assertion. Karl Brugmann, for example, writes, “For the Passive Voice there were originally no special and characteristic endings in the Indo-Germanic [Indo-European] languages. All so-called passive forms in the verb finite are either middle or active” (A Comparative Grammar of the Indo-Germanic Languages, Vol. 4, Morphology Part 3, trans. R. Seymour Conway and W. H. D. Rouse [New York: B. Westermann and Co., 1895], 515).[↩]

- According to Conrad, this middle/passive morphoparadigm would be marked as “subject-focused” in opposition to a “simple” morphoparadigm, unmarked with regard to subject-focus—what we know as “active” voice (“New Observations on Voice,” 7).[↩]

- Perhaps most relevant to the issue at hand is Conrad’s plea: “What I would urge is that we cease referring to the so-called ‘Deponent Verbs’ by that name and that we henceforth pay attention to their principal parts and the morphoparadigm(s) in which the verb is found, interpreting the verb’s meaning in terms intelligible from those morphoparadigms” (ibid., 9).[↩]

- “Ancient Greek Voice,” available at https://pages.wustl.edu/cwconrad/ancient-greek-voice.[↩]

- The Middle Voice in Ancient Greek: A Study of Polysemy, Amsterdan Studies in Classical Philology 11 (Leiden: Brill, 2003). Allen’s dissertation is a broader exploration of the middle in Ancient Greek, but he makes points that are significant to the issue at hand.[↩]

- Ibid., 35. Oppositional middles are middle occurrences of a verb which has both an active and middle form.[↩]

- Ibid., 36.[↩]

- Ibid., 111.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Allen’s “Fig. 1” is taken from page 109 and “Fig. 2” from page 117.[↩]

- “Deponency in Koine Greek: The Grammatical Question and the Lexicographical Dilemma,” Trinity Journal 24 (NS) (Spring 2003), 55–76.[↩]

- Pennington, “Setting Aside Deponency,” 182.[↩]

- Ibid., 187.[↩]

- Kemmer’s cross-linguistic study is very helpful, particularly in her categorization of the types of events represented by middles. The Middle Voice, Typological Studies in Language 23 (Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1993).[↩]

- Pennington, “Setting Aside Deponency,” 187.[↩]

- See http://jonathanpennington.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/test-driving-the-theory-handout-pennington.pdf and http://jonathanpennington.com/wp-content/ themes/jtp2011/AfterDeponencyPaperHandoutPenningtonSBL2012.pdf; also Campbell, 100, fn. 46).[↩]

- Advances in the Study of Greek: New Insights for Reading the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2015), 19. In email correspondence, Campbell indicated that the fourth chapter of this work, “Deponency and the Middle Voice,” here cited, is basically a revision of his 2010 Society of Biblical Literature presentation.[↩]

- “Greek Deponency: The Historical Perspective” in Biblical Greek in Context: Essays in Honour of John A. L. Lee, ed. T. Evans and J. Aitken (Leuven: Peeters, 2015), 190.[↩]

- While I do not have access to that paper and am not aware that is has yet been published, Campbell, who was present, indicates that Porter came out against deponency (Advances in the Study of Greek, 98).[↩]

- Advances in the Study of Greek, 98.[↩]

- Both Pennington (“Setting Aside Deponency”) and Campbell (“Deponency and the Middle Voice”) have pointed out these two major areas of challenge or possible objection. Another challenge worthy of addressing, brought to my attention by my colleague Brian Hand, is the issue of verbs that are middle-only in one principal part, and yet take active endings in another principal part (for instance, a verb that is middle-only in the present tense-form, but has a stem change and active endings in the aorist tense-form). There is value in working through and discussing these challenges and complexities as part of a balanced approach to the issue.[↩]

- For an example of a verb whose aorist passive form may communicate a middle idea, see the discussion of συγχέω in the concluding section of this article.[↩]

- “Voice, Aspect, and Aktionsart: Middle and Passive in Ancient Greek,” in Voice: Form and Function, ed. Barbara Fox and Paul J. Hopper (Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1994), 29.[↩]

- Pennington, “Setting Aside Deponency,” 194. I am not sure I exactly agree with the way he puts this—nevertheless it seems like he may be on to something with his general line of argument here.[↩]

- Ibid. See also M. H. Klaiman, Grammatical Voice, Cambridge Studies in Linguistics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).[↩]

- “On the whole the conclusion must be arrived at that the New Testament writers were perfectly capable of preserving the distinction between the active and the middle” (Friedrich W. Blass, Grammar of New Testament Greek, trans. H. St. J. Thackeray [1898; repr., Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2010], 186).[↩]

- Even the most unwavering continuationist ought to take some pause in appealing to the concept of deponency in 1 Corinthians 13:8 with regard to the word translated “will cease.” This verb, παύω occurs in the active voice in Koine (see 1 Pet 3:10). And in extrabiblical Koine literature, this verb even occurs in the future active. Deponency seems to be something of an interloper in this conversation. And yet how many times have appeals to deponency been made in argumentation regarding this passage? Changing one’s view on deponency probably should not change one’s view on tongues. But better sensitivity to the range of meanings that can be signaled by the Greek middle might remove from some of our discussions concepts that may actually be unhelpful to the discussion. If some of those in this discussion could stop dismissing the word as a deponent on the one hand, or on the other hand trying to freight the term with meaning without a full-orbed understanding of the middle voice, perhaps there could be more meaningful discussion about the role of this verb’s middle voice. Whether or not the middle voice is a significant factor in how the voice is interpreted, some of the unhelpful contributions to the discussion might just cease (in and of themselves for that matter) if both perspectives embraced a better understanding of the issues surrounding “deponency” and overly simplistic understandings of the middle voice.[↩]

- An oppositional middle is a middle verb form of a verb that also occurs in the active voice.[↩]

- Helpful lists from Kemmer and Miller are available on Conrad’s page: https://pages.wustl.edu/cwconrad/ancient-greek-voice.[↩]

- Whether or not the exegete wishes to pursue this level of analysis, it is now at least open to him, whereas previously he may have simply waved the form aside as “deponent” and moved along without another thought.[↩]

- For discussion of Acts 2:6 as a mental-process middle, see Rachel Aubrey, “Motivated Categories, Middle Voice, and Passive Morphology” in The Greek Verb Revisited: A Fresh Approach for Biblical Exegesis, ed. Steven E. Runge and Christopher J. Fresch (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016), 601.[↩]

- Rodney J. Decker, Reading Koine Greek: An Introduction and Integrated Workbook (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2014), 15.9.[↩]