On Being Conservative

Last week the satirical news site Babylon Bee made the national news with a post distasteful to some, mocking a health-and-wealth guru after she proved herself a fraud by dying. While that story was making the headlines, a less popular post titled “Conservative Christian Trying To Remember What He’s Supposed To Be Conserving” caught my attention. It did so because in the conservative evangelical world, there is often little agreement on what should be conserved. Some conserve a whole confessional heritage, others a block of “fundamentals,” and others a centerpiece of theology regarded as the linchpin of the Christian faith (e.g., inerrancy or “the gospel”); some conserve a formal liturgy, others a hymn tradition rich in doctrine, and others some flagging worship style that has been left behind by the progressives; some cling to a nostalgic way of life when things were simpler and common grace more abundant; and still others don’t care so long as a Republican is in the White House trying to stop abortion and get the Bible and prayer back into the public schools. Hence the Babylon Bee’s satirical confusion—what are Christian conservatives actually conserving, if anything?

As a self-identifying “conservative,” I mean by the label that I am a foundationalist. That is, I believe that within God’s order are fixed and inalienable standards of right and wrong in the spheres of truth, goodness, beauty, and in fact every philosophical sphere. The standard of right in each case is defined by God and is not subject to progress. So while the world around me experiments continually with alternative universes in which goodness, beauty, and truth are other than what God defines them to be, I refuse to do so on principle, viz., the conservative principle.

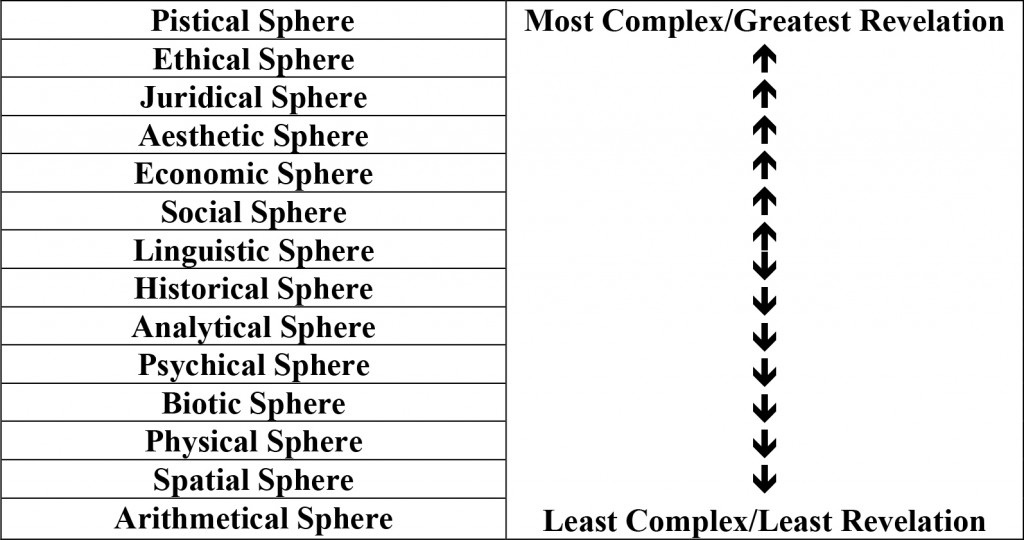

In the spheres of truth (what I know/believe) and goodness (what I ought/do) God supplies in his written Word a wealth of propositional data, and being “conservative” in these matters largely reduces to believing God’s Word: to be conservative is to believe in biblical inerrancy. Other philosophical spheres (e.g., beauty), however, are not so fully addressed in Scripture, a state of affairs captured succinctly in J. M. Spier’s Introduction to Philosophy. On p. 44 of this volume Spier suggests fourteen “spheres” which, while because of their increasing simplicity are the object of progressively less and less propositional data in Scripture, still remain fixed in the divine mind. IOW, everything is foundational to God, even what is not explicitly expressed in Scripture:

As we proceed down this list we (arguably) find less direct biblical revelation at each successive level, not because God is neutral/undecided/ambivalent about these issues, but because these issues are progressively simpler and less objectionable to the depraved mind (i.e., few people doubt that 2+2=4—not because the Bible tells me this statement is true in so many words, but because the arithmetic first principles of the Christian worldview are assumed and accepted by virtually all people without objection).

The conservative admits that warrant for identifying truth and ought in the interior disciplines is sometimes difficult (for an interesting attempt to do this, see Roy Clouser, The Myth of Religious Neutrality), but approaches the task by summarily denying the idea of neutrality (i.e., non-foundational data) in any sphere, and by affirming the need to discover and embrace what is right in every sphere. This contrasts with the non-conservative, who believes that God’s revelation is sufficient only for spiritual truth, that neutrality is a common feature of many philosophical spheres, and that there is consequently little or nothing to conserve in them.

Being a conservative is not an easy thing in a world (and sometimes in churches) that embrace progressivism (the opposite of conservatism). But the foundational nature of God’s truth system cannot ultimately survive without it.

Thanks, Mark. Good concise summary, and I like the term “foundationalist.”

One thing I would add (that reflects my recent CCGG talk) is that while you are right that matters of beauty are addressed with far less propositional precision in Scripture than matters of doctrine and morality, this does not mean that beauty is not addressed in Scripture. Beauty is, in fact, addressed, but in ways beyond mere propositions. Scripture itself employs aesthetic forms in its communication of truth, and those aesthetic forms (just as inspired and authoritative as the propositions) should serve to regulate what we think about beauty in our culture.

I think I get what you are saying, but it would be helpful if all the terms were in English. Or at least the English of the common man! Which I say to point out that one of the difficulties in communicating these ideas is the proliferation of jargon.